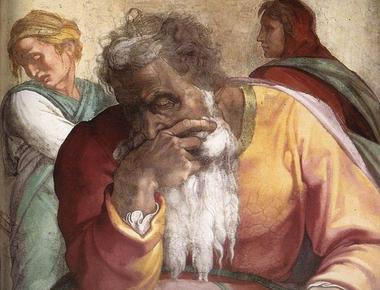

On 12 September 1830 Newman preached a sermon in the University Church entitled “Jeremiah, A Lesson for the Disappointed.” It has not, so far as I am aware, ever attracted a great deal of attention. Though it was later published in Parochial and Plain Sermons—“the most important publication not only of Newman’s Protestant days, but of his life,” as Owen Chadwick once averred—it had to wait til volume eight for inclusion: hardly typical of “The Very Best Of …” territory.

That is fitting in a way, however. For the whole topic of “Jeremiah, A Lesson for the Disappointed” is the fact of being overlooked, of deserving recognition but not getting it, of striving and failing—or rather, of seeming to fail.