Newman’s description of self-denial in light of the invisible world can help us to examine and renew three fundamental relationships: with God, our neighbor, and the natural world.

Newman’s description of self-denial in light of the invisible world can help us to examine and renew three fundamental relationships: with God, our neighbor, and the natural world.

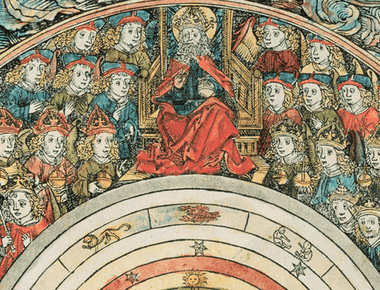

When I first read the late Fr. John O’Malley’s survey text What Happened at Vatican II (2008), I was struck by a passage in the conclusion. O’Malley gave a tantalizing rundown of the “ghosts” present on the council floor—the popes, theologians, philosophers, and politicians whose lives and legacies had indelibly marked the Catholic world. These voices from the past had shaped, positively or negatively (sometimes both), the work of the council fathers:

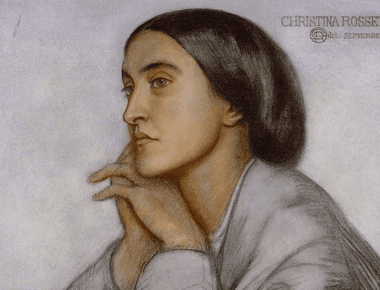

Introduced here are three examples of lay women who were deeply influenced by Newman in particular as well as by the greater Oxford Movement. These three women had varying degrees of interaction with Newman personally.

In the scholarly literature, John Locke (1632–1704) features as a formative influence on Newman’s philosophical thought. What usually gets highlighted, for example in the Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, are Newman’s criticism of Locke’s notion of degreed assent and his call for a broader and more nuanced account of the rationality of religious belief. However, some have argued that the Grammar largely focuses on the psychological conditions of religious belief.

Despite their differences, and although Newman and Browning never met, they shared similar life experiences, and literary techniques, and both were concerned with the justification of Christianity, as well as the struggle between faith and doubt.

An important theological theme in the Christian tradition is that of the divine ideas or <em>logoi</em> in the mind or Word of God by which God knows and loves in himself eternally all the ways that creatures can or do participate in a living likeness of him.

QUICK LINKS