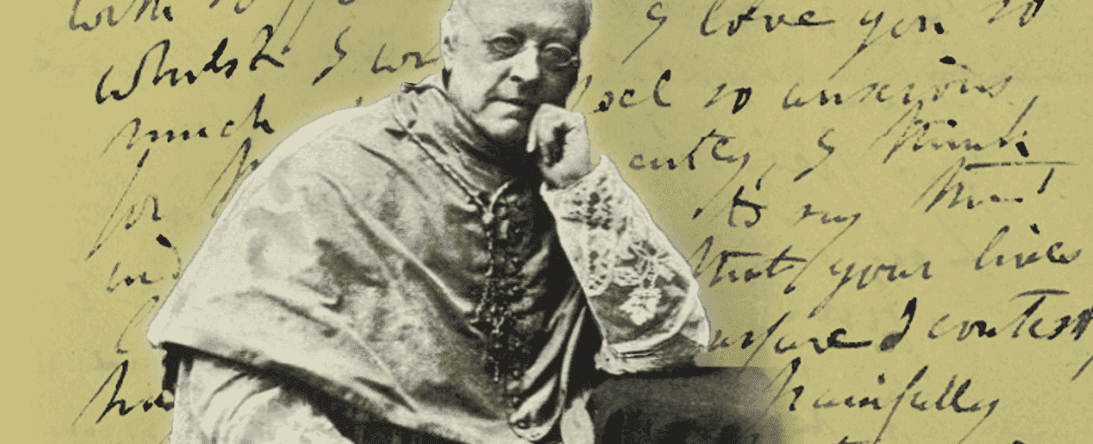

William Bernard Ullathorne: His Life and Legacy

William Bernard Ullathorne (1806–1889) was a wise and humble man known for his devotion to the priests and nuns under his charge. Although he had a strong preference for monastic life, Ullathorne willingly served the church whenever he was called. He held many positions throughout his life such as first Vicar General for Australia (1832–1840), Vicar Apostolic for the Western District (1846–1848), Vicar Apostolic for the Central District (1848–1850), first Bishop of Birmingham (1850–1888), and titular Archbishop of Cabasa (1888–1889). Through these positions, he was able to form generations of priests, start religious orders for women, and advise prominent men of the church, such as John Henry Newman and Henry Edward Manning. He was also a prolific writer who authored many texts including but not limited to: The Immaculate Conception of the Mother of God (1855)1, Ecclesiastical Discourses Delivered on Special Occasions (1876), The Groundwork of the Christian Virtues (1882), Christian Patience (1886), and The Endowments of Man (1888). His life was one of prayer, continuous learning, and mentorship.

Early Life

William Ullathorne was born to Hannah Longstaff (died 1860) and William Ullathorne (died 1829) on 7 May 1806 in Pocklington, a small town near Yorkshire, England. He was the oldest of ten children and was raised Catholic despite the shortage of priests in Pocklington.2 Ullathorne was educated to be a businessman like his father;3 however, when the Ullathorne family moved to Scarborough around 1817,4 William was quite taken by the sea and instead desired to become a sailor.5 It was during his time on the ship Anne’s Resolution that William Ullathorne met the Catholic Craythorne family and experienced a conversion of heart.6 Ullathorne was raised Catholic, but had not practiced his faith to the fullest: “We had our Sundays at home, but in the weekdays I fear our prayers were short.”7 But, after attending mass with Mr. Craythorne one Sunday, Ullathorne felt called to religious life, writing, “What I beheld threw me into a cold shiver, and turned my heart completely round myself. I saw the claim of God upon me.”8 In February 1823, Ullathorne began studying for the priesthood at the Benedictine Priory of St. Gregory at Downside.9

Religious Formation

Ullathorne studied to be a priest from February 1823 to 24 September 1831 when he was ordained at Ushaw.10 On 12 March 1824, Ullathorne received his monastic habit and took the name Bernard, making his full name William Bernard Ullathorne.11 He had a reputation for being quite serious and involved with his studies. Ullathorne read constantly and was especially interested in the church fathers, which won him the nickname “Old Plato.”12 A contemporary of Ullathorne, Dom Ephrem Pratt, recalled that when in the midst of discussions Ullathorne’s peers would ask, “What does the old man think?” referencing Ullathorne. In the second volume of The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, Butler describes him as a “self-made theologian” who was “widely read in [the church] Fathers and theologians” and as being “highly intelligent.”13 Ullathorne was greatly respected by others for both his wisdom and his genuine care for others, which is demonstrated in his religious work.

Early Ministry

Ullathorne’s religious ministry predominantly involved the formation of his clergy and caring for religious sisters. He was appointed Vicar General for Australia in 1831 and ministered there for about three years. When he arrived, Australia was transitioning from a penal settlement to a British colony.14 Ullathorne was an advocate for Australia’s convict population, and his efforts led to the end of convict settlements in Australia.15 During his ministry to convicts, Ullathorne preached against drunkenness and vice in one of his most successful sermons, The Drunkard.16 Ullathorne recounted his missionary work in Australia in his book, The Catholic Mission in Australasia.17

In 1841, Ullathorne went to Coventry to serve the Benedictine mission and met Mother Margaret Mary Hallahan (1806–1868).18 Together, the two founded the English Congregation of St. Catherine of Siena of the Third Order of St. Dominic in December 1845 with Mother Margaret Mary Hallahan as the first Prioress.19 Ullathorne’s devotion to the sisters is evident in his correspondence with them, which can be found in the NINS Digital Collection’s Stone Priory Collection. He was equally devoted to the priests who fell under his care, and “to any priest in trouble he was always the kind, sympathetic, Father.”20 One priest who greatly benefited from Ullathorne’s paternal guidance was John Henry Newman.

Ullathorne’s Relationship with Newman

Ullathorne first met Newman during his visit to the Oxford convents at Maryvale in 1846, and he personally invited Newman to his consecration as Bishop of Hetalonia at Coventry on 21 June 1846.21 However, the pleasant start to their relationship did not last long. When Ullathorne came to Birmingham as Vicar Apostolic of the Central District in 1848,22 he and Newman became engaged in a controversy over Faber’s proposed English adaptation of the Italian Lives of Modern Saints. Newman supported Faber’s efforts to translate the books into English, but Ullathorne believed the book was not suited for an English audience.23 The pair exchanged numerous letters on the subject—beginning with Newman’s 10 October 1848 letter to Ullathorne—and Newman eventually acquiesced to Ullathorne.24

The beginning of their close personal relationship is marked by Ullathorne’s 29 November 1848 letter to Newman, which expresses his love for Newman and sorrow for how Newman had been previously treated. Almost a year later, on 27 October 1850, Newman preached his famous sermon—Christ Upon the Waters—at Ullathorne’s consecration as the first Bishop of Birmingham. The pair exchanged many letters thereafter, and Ullathorne became an episcopal defender of Newman. As their relationship deepened, Ullathorne became acutely aware of Newman’s holiness and wrote in a letter, “I felt annihilated in his presence: there is a Saint in that man!”25

Nothing better illustrates the relationship between Ullathorne and Newman than Ullathorne’s own words in Christian Patience:

My Dear Lord Cardinal [Newman],

I do not forget that your first public appearance in the Catholic Church was at my consecration to the Episcopate, and that since that time forty years of our lives have passed, during which you have honoured me with a friendship and a confidence that have much enriched my life. Deeply sensible of the incalculable services which you have rendered to the Church at large by your writings, and to this Diocese of your residence in particular by the high and complete character of your virtues, by your zeal for souls, and by the influence of your presence in the midst of us, I wish to convey to you the expression of my affection, veneration, and gratitude, by the dedication of this book to your name. It is the last work of any importance that I shall ever write, and I can only wish that it were more worthy of your patronage.26

End of Life

Although Ullathorne made many friends and achieved great things during his ministry to the church, he always longed to return to the monastic life he experienced at the Benedictine Priory. He said, “I was made for a hermit, and tried hard when a novice to get leave to go to the French Trappists; but other people would not let me go.”27 Ullathorne’s sense of duty to the church and to others compelled him to work until 1888 when he retired due to his failing health. His private, personal piety was revealed in his last days through his fervent and frequent prayer. As the prayers for the dying were being prayed over Ullathorne with the words, “from the snares of the devil deliver him, O Lord,” Ullathorne famously interjected with, “the devil’s an ass.”28 Ullathorne died on St. Benedict’s Day, 21 March 1889, and was buried at Stone near his mother and Mother Margaret Hallahan according to his wishes. He was the last surviving Vicar Apostolic.29

Newman expressed his admiration for Ullathorne’s dedication to the Catholic Church in his 1871 address:

My Lord, we come before you with this address, young and old; but whatever be our age, according to the years that we have had experience of your governance, we gratefully recognize in you a vigilant, unwearied Pastor; a tender Father; a Friend in need; an upright, wise, and equitable Ruler; a superior who inspires confidence by bestowing it; the zealous Teacher of his people; the Champion by word and pen of Catholic interests, religious and social; the Defender of the defenceless; the Vindicator of our sacred ordinances amid the conflict of political parties and the violence of theological hostility; a faithful Servant of his Lord, who by his life and conduct claims that cheerful obedience which we hereby, with a full heart, offer to you.30

1 William Bernard Ullathorne, From Cabin Boy to Archbishop: The Autobiography of Archbishop Ullathorne (Burns Oates, 1941), 2, 10. This autobiography was published posthumously from a manuscript located at St. Dominic’s convent in Stone, England.

2 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 326.

3 Ullathorne, From Cabin Boy to Archbishop, 11.

4 Ullathorne, From Cabin Boy to Archbishop, 19–21.

5 Ullathorne, From Cabin Boy to Archbishop, 8.

6 Ullathorne, From Cabin Boy to Archbishop, 21.

7 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 326.

8 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 327.

9 William Bernard Ullathorne, Christian Patience: The Strength and Discipline of the Soul, 6th ed.(Burns & Oates Limited, 1886), vii.

10 Dom Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne 1806–1889 (Benziger Brothers, 1926), 2:222.

11 William Bernard Ullathorne, The Catholic Mission in Australasia (Rockliff & Duckworth, 1837).

12 Dom Butler, The Life & Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 1806–1889 (Burns, Oates, and Washbourne Ltd., 1926), 1:307.

13 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 330.

14 Butler, The Life & Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 1:155.

15 Newman recounts this controversy in his book, A Letter to the Rev. E.B. Pusey.

16 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:292.

17 Anon, “The Most Reverend William Bernard Ullathorne, O.S.B.,” The Dublin Review 8, no. 2 (July 1889): 73.

18 Albert Thorold, “Ullathorne—The Man,” The Downside Review 44, no. 2 (May 1926): 139.

19 Thorold, “Ullathorne—The Man,” 141–42.

20 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:191.

21 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:283–84.

22 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:294–96.

23 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:194.

24 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 327.

25 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 327–28.

26 Bellenger, “The Normal State of the Church,” 329.

27 Dom Bellenger, “‘The Normal State of the Church’: William Bernard Ullathorne, First Bishop of Birmingham,” British Catholic History 25, no. 2 (October 2000): 325–26.

28 Newman praises this work, saying, “If anyone wishes to see our doctrine drawn out in a treatise of the present day, he should have recourse to Dr Ullathorne’s Exposition of the Immaculate Conception, a work full of instruction and of the first authority.” Newman, A Letter to the Rev. E.B. Pusey, D.D. on His Recent Eirenicon, 3rd ed.,(Longman, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1866), 130.

29 Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 2:295.

30 Dom Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne 1806–1889, 2:222.

Angela Baker

Angela Baker is a fourth-year Psychology student at the University of Pittsburgh with a focus on the intersections of psychology and law. She was an intern at the National Institute for Newman Studies (NINS) during the summer of 2024, and now serves as the Digital Humanities and Editorial Specialist at NINS.

QUICK LINKS