Reading Louis Bouyer with Keith Lemna: A Review of The Apocalypse of Wisdom

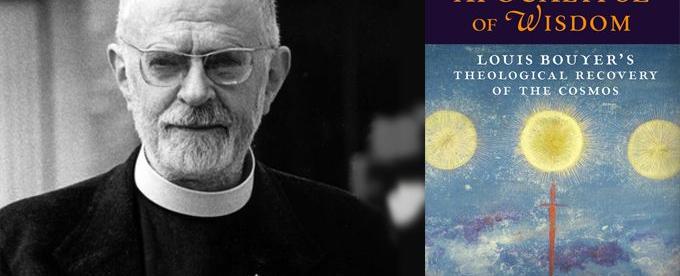

The Apocalypse of Wisdom: Louis Bouyer's Theological Recovery of the Cosmos. Keith Lemna. Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2019. Pages: xxx + 488. Paper, $22.95. ISBN: 9781621384717.

“Enlightenment scientism and modern variations of orthodox Christian theology … have worked together in unwitting symbiosis to empty the world of its harmonious mind and vitality. ... The mechanical way of seeing the world, radically partitioning subject from object, is increasingly recognized to have led to a social ethos that drove civilizational initiatives whose outcome was the mass destruction of plant and animal life, the eclipse of beauty in culture, and ultimately imminent apocalyptical reckoning. The beauty and order of being, constitutive attributes of the world as cosmos, were lost from view. Can we ever again catch sight of this beauty, is it real, and, if so, can human wisdom ever be made to harmonize with it?” (Keith Lemna, The Apocalypse of Wisdom, xi-xii)

In 1982, French Oratorian Louis Bouyer (1913–2004), most well-known in the United States for his liturgical scholarship, published Cosmos: The World and the Glory of God, one volume of what would become a nine-volume systematic theology written between 1957 and 1994 and organized into Trilogies of Economy, Theology, and Knowledge of Faith. In Cosmos, Bouyer took on the theological roots and ecological consequences of the cosmological question noted by Keith Lemna. Bouyer sought to integrate theological, philosophical, and scientific thought to recover a sense of the cosmos as a harmonious whole, a sapiential understanding of the meaningfulness of that whole, and a future-oriented, apocalyptic, and anticipatory Christian cosmology. He rediscovered the cosmos as a gift of the Creator, radiant with the Creator's light, while recovering and developing the theandric humanism of "those Church Fathers who elaborated the Pauline and wider biblical cosmology in confrontation with Greco-Roman philosophy" (xii-xv).

The primary purpose of Lemna's masterful book The Apocalypse of Wisdom: Louis Bouyer's Theological Recovery of the Cosmos is to shed light on the "twists and turns of the path Bouyer charts in Cosmos" (xiii). But The Apocalypse of Wisdom is no mere book-about-a-book. Lemna's commentary on Bouyer's Cosmos is thorough and insightful beyond expectation. Lemna engages not only the text of Cosmos, but Bouyer's historical context and the lion's share of his corpus as well. That historical context includes both Bouyer's biography and a vast network of thinkers and writers who are engaged in an exploration of the cosmos and the place of the human being in it. Hans Urs von Balthasar, John Henry Newman, Sergei Bulgakov, Vladimir Lossky, the Inklings (including J. R. R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis), Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Rudolf Otto, Mircea Eliade, depth psychologists (Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud among them), sociologists of religion (including Émile Durkheim and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl), Romano Guardini, a diverse group of philosophers (Edmund Husserl , David Hume, Alfred North Whitehead, Maurice Blondel, and Henri Bergson to name but a few), Rudolf Bultmann, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Pavel Florensky, Jacob Böhme, Franz von Baader, Louis Bautain, Anton Günther, Olivier Costa de Beauregard, and many others take their place alongside Thomas Aquinas and the Church Fathers in Lemna's narrative because their work helped to create the world in which Bouyer wrote. And since Lemna's knowledge of Bouyer's life and works is encyclopedic, The Apocalypse of Wisdom accomplishes much more than its stated goal of explaining Cosmos. It introduces readers unfamiliar with Bouyer to his entire life and work as a harmonious whole, fittingly seeking to understand Bouyer as Bouyer understood the cosmos.

Of particular interest to readers of the Newman Review will be the many ties Lemna notes between the lives and works of Bouyer and Newman. Bouyer authored Newman: His Life and Spirituality and Newman's Vision of Faith: A Theology for Times of General Apostasy. Both Oratorians were converts (Bouyer from Lutheranism), and Athanasius, one of Newman's great heroes among the Church Fathers, was the focus of Bouyer's licentiate thesis and doctoral dissertation. Newman's writing provided life-long inspiration for Bouyer's theological reflections, and Lemna's book highlights Newman's enduring presence in the chapters of Cosmos. Since The Apocalypse of Wisdom's information density makes it impossible to summarize succinctly, I'll use Newman as an exemplar of the sorts of connections Lemna makes between Bouyer and the many scholars listed above.

Lemna's introduction sketches broadly the questions Bouyer is engaging and locates The Apocalypse of Wisdom relative to other scholarly works on the French Oratorian's thought. Then follows "Imagination and Wisdom" in which Lemna does with Bouyer as Bouyer had done in his writings on Newman: he places Bouyer's thought in the context of his biography, drawing on his Memoirs and other writings. Highlighted are the formative experience of the landscapes of Bouyer's youth and his early encounters with the work of Newman and Bulgakov; the influence of ancient Christian Platonism's sense of the relationship between universal concept and concrete experience on seventeenth century Cambridge Platonists, and through them, on Bouyer's generation; and the importance of imagination and symbol in the twentieth century literary response to science's disenchantment of the world. Inspired by Bulgakov (whose preaching he heard in Paris), Bouyer followed a sophiological "third way" between Christian strategies of escape from the world and accommodation to it; his cosmology is, according to Lemna, "rooted in both apocalyptic imagination and the theology of Wisdom" (40).

The next nine chapters of Lemna's book follow Cosmos's outline, with each chapter dedicated to unravelling the riches of between one and five chapters of Cosmos. "Myth and Knowledge of the World" draws out Bouyer's central argument as expressed in the first two chapters of Cosmos: "Myth and the mythopoetic function of creative imagination are essential to the progress of both rational thinking and divine revelation" (41). Already Lemna's masterful weaving together of Bouyer's other works is on display; he draws on five of the other volumes of Bouyer's systematic theology (The Invisible Father, The Eternal Son, and Le Consolateur [The Trilogy on Theology], and Sophia and The Christian Mystery [from The Trilogy on Knowledge of Faith]), plus at least three of Bouyer's other book-length works to highlight ideas Bouyer held firmly throughout his life, to make more explicit ideas that are only implicit or presupposed in Cosmos, or to aid Lemna in accurately paraphrasing Bouyer's thought. This engagement with other works of Bouyer is also how Lemna makes his readers aware of the enduring presence of Newman and other thinkers in Cosmos. He turns, for example, to The Invisible Father to show how Newman's distinction between real apprehension/assent and notional apprehension/assent becomes the basis for Bouyer's insistence that "we can discover God only in and through our experience of the world, and, inversely, that we can discover the world in its truest meaning only through knowledge of the divine, transcendent source of being ... 'Abstract reasons for believing in God have never been the source for any man's faith'" (45, using Invisible Father, 3). Newman distinguishes between the poetic, scientific, and practical ways of teaching exemplified by Sts. Benedict, Dominic, and Ignatius of Loyola respectively, and Lemna argues that "the entire weight of Bouyer's work suggests that we have become hardened to the logic of St. Benedict's poetic way" (77).

"From Myth to Wisdom (I): The Old Testament" is where Lemna makes clear how Bouyer understands the relationship between Cosmos and the rest of the trilogy of which it is a part. As the Fall in Genesis has three successive moments (a personal by Adam and Eve, a cosmic by the angels, and a social at the Tower of Babel), so is Bouyer's Trilogy on the Economy organized: his Mary, The Seat of Wisdom is a supernatural anthropology, Cosmos is a supernatural cosmology, and The Church of God is a supernatural sociology. Drawing on Bouyer's theology of inspiration as it is articulated in Le Consolateur, Lemna illuminates chapters three through seven of Cosmos by noting that Bouyer evokes Newman's commendation of the Alexandrian Church Fathers of the third century for their practice of the arcani disciplina to distinguish between Wisdom and gnosis: "Newman understood that this discipline was a method to translate the content of divine revelation to the stage of advance in the spiritual path of the neophyte. It was not a false gnosis, a power play, a holding back of secrets in order to bolster the authority of bishops, priests, and catechists" (85). In "From Myth to Wisdom (II): Philosophy," Lemna continues to stress Newman's influence on Bouyer, but notes too how Bouyer develops Newman's line of thought. Newman's stress on revelation developing in time and history as a living, fecund, and moving reality that makes possible the development of doctrine is applied by Bouyer to the entirety of creation, "centering all ideas on the Idea of ideas, the Mystery of God from the heart of divine Wisdom made present in the flesh of Christ. For both Oratorians, humanity does not unite to the ideal world by fleeing from the sensible plane of existence" (154). Though both Newman and Bouyer hold that the world of ideas is united to humanity by God in the Incarnate Word, it is Bouyer, Lemna notes, who systematically develops this understanding in its vastest cosmic scope, and he does so in a sapiential direction that is ever mindful of the uniqueness of the scriptural vision of the relationship between God and the world.

In "Christology and Cosmology" Lemna details the extensive exegesis of New Testament cosmology Bouyer did in his other books and which he presumes in writing Cosmos. Pointing to the New Testament's metamorphosis of the eschatological Celestial Man of the Old Testament in light of what is new in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, Lemna demonstrates the deep ties between Bouyer's Cosmology and his Christology. Lemna credits Bouyer's early reading of Newman on the development of doctrine for allowing him to notice Athanasius's distinction in unity between divine and created Wisdom, which "laid the groundwork for a sophiological understanding of God's relationship to creation" (173). Without using the term, Lemna says, Bouyer holds to the eternal humanity of Jesus, seeing in Bulgakov and others a development of patristic sapiential Christology. "The Loss of the Theoanthropocosmic Synthesis" traces how Bouyer narrates that Christology's fate when faced with the advance of scientific modes of thought beginning in the Middle Ages. Bouyer counsels that scientific knowledge must leave room for other sorts of knowledge (an idea which is in accord with Newman), and Lemna sees in Bouyer a call to redevelop the practice and theology of the icon in order to see the world as it ought to be seen.

Lemna groups the above chapters in Part I of The Apocalypse of Wisdom, titled “Cosmology in History” because they engage the chapters of Cosmos that are more genetic-phenomenological in content; that is, they give an account of Bouyer's "history of cosmology from the standpoint of Christian faith" (423). Lemna rounds out this first part of his book with "The Recovery of Poetic Wisdom" in which he treats Bouyer's connection of Wisdom to the vocation of the poet. Here the poetic theology of the Russian sophiologists and the work of nineteenth-century Catholic sophiological philosophers take center stage. Lemna makes the case that "Bouyer sees the most recent advancements of modern science as potential paths opening human thought to a unifying, "sophianic" view of creation, particularly with the advent of depth psychology" (228). Lemna then groups together in Part II, “Exitus-Reditus,” chapters that address the more metaphysical portions of Cosmos. Here Lemna notes the parallels between Bouyer's organization of themes in the second part of Cosmos and Thomas Aquinas's organization of the Summa Theologiae, with all of creation brought into being in God and ending in Christ in the general resurrection.

Part II begins with "Trinitarian Wisdom," which explores Bouyer's personalist rendering of the triune love of God, his vision of the world that lives in that kenotic love, and what he means when he speaks of "created Wisdom." Here again, Lemna casts his net wide and deep into Bouyer's bibliography, allowing all his works to inform our understanding of Cosmos and vice versa. Collectively, Lemna says, Bouyer's works show that the mystics possess greater normative authority for him than do the Neoscholastic theologians on the Trinity, though Bouyer does not oppose the mystics to Augustine and Aquinas.

Newman returns in "Angels and the Cosmic Liturgy," in which Lemna shows that Bouyer's cosmology is "an expansion of Newman's sacramental principle, enunciated in both the Apologia and Parochial and Plain Sermons," and that Bouyer "understands the sapiential direction that Bulgakov inspired him to follow as 'the crowning of that vision of the world that Newman helped [him] to attain'" (305). Elsewhere Bouyer calls Bulgakov's angelology a Christian cosmology; in Cosmos he calls Newman's sacramental system as an "angelological cosmology." For both Newman and Bouyer, the invisible world of the angels is the deepest dimension of our world, the dimension we experience when we participate in the liturgy.

A consideration of angels leads naturally to a discussion of the relationship between matter and spirit, so "Human Corporeity and the Mystical Body" is Lemna's account of Bouyer's history of the Christian microcosm "in light of modern science, his theology of sin and cosmic evil, and his theology of the New Adam and the Church as macrocosm" (343). In this development, rather than characterizing Bouyer as having been influenced by Newman, Lemna understands both Newman and Bouyer to have been influenced by Bishop Joseph Butler's The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, which argued (against Deists) that God intervenes directly in creation.

Bouyer ends Cosmos by talking about the meaning of the cosmos being revealed in the eschatological and nuptial disclosures in the Apocalypse of John. "Bouyer teaches," says Lemna in his penultimate chapter, "The Eschatological and Nuptial Cosmos," that "the driving purpose embedded within the metaphysical sinews of creation from the very beginning was to be united in nuptial communion with the Immolated Lamb of God in and through the eschatological Church. The meaning of creation is unveiled only with the definitive apocalypse of Wisdom in the Parousia" (381). Bouyer, like Newman before him, associated the celestial woman of Revelation 12 with the Theotokos.

Having commented on the entirety of Cosmos, Lemna sets out in "The Return of the King" to discuss the organic link between its phenomenological and metaphysical parts, which Lemna finds by considering "the transfiguration of the royal myth by biblical revelation summed up in the Paschal Mystery of Christ" (424). Bouyer's theology is an extensive commentary on Scripture that is shaped by Christian liturgical experience, and its liturgical and ritual dimension "penetrates down to the philosophical level" (428). In The Idea of a University Newman had argued that natural theology is the architectonic science to which other sciences must be compelled to order or contextualize their understanding; other sciences are methodologically inadequate to the task of filling the sapiential void left if theology is removed. Bouyer, Lemna contends, offers a counter-story of cosmic development to other sciences "which is nourished by a very different and well-explicated imaginary that relies on a very different image of human perfection and surrounding symbols than Neodarwinism provides" (433). He understood Newman to express the beauty and luminosity of the cosmos even while seeing its dark face more fearsomely than anyone else. Lemna finds Bouyer's cosmovision to be unique in twentieth-century Western theology for its critical embrace of Eastern Christianity's sophiology and important for our own time when the very existence of a metaphysical dimension is disputed.

The only criticism I can make of this otherwise fabulous book regards its shallow engagement with the work of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin given that Lemna chooses to put the work of these two great French thinkers of the twentieth century up next to each other. Lemna rightly notes in his introduction that Bouyer took on the theological Problematik identified by Teilhard (though he intended to provide a broader interpretative horizon for modern cosmology) (xviii), and he credits Teilhard and the ressourcement theologians of the early twentieth century with understanding the intimate link between Cosmology and Christology necessary to put forth a comprehensive theology of creation (157). But the paraphrasing of Teilhard's thought in The Apocalypse of Wisdom is imprecise, and due to a lack of citations (e.g., 254–55) it is unclear whether the sloppiness is Bouyer's or Lemna's. Fortunately, Lemna's argument doesn't need a contrast between Bouyer's thought and that of Teilhard (or Teilhardiens) to be persuasive. My own deep appreciation for Teilhard's work survives undiminished even as Lemna's book inspires my desire to read Cosmos. For this reader, at least, Lemna achieved his goal of fostering appreciation of Bouyer's theology in the English-speaking world.

Laura Eloe

Graduate Instructor, University of Dayton

Laura Eloe received her PhD in Theology from the University of Dayton in 2019. She taught mathematics and theology for 29 years at Chaminade Julienne High School in Dayton, Ohio and mathematics at the University of Dayton and Utah State University. She currently works in the office of the Fr. William J. Ferree, SM, Chair of Social Justice, and teaches in the graduate programs in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Dayton. She is a member of the Board of the American Teilhard Association, serving as chair of the Publication Committee and Editor of Teilhard Studies.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS