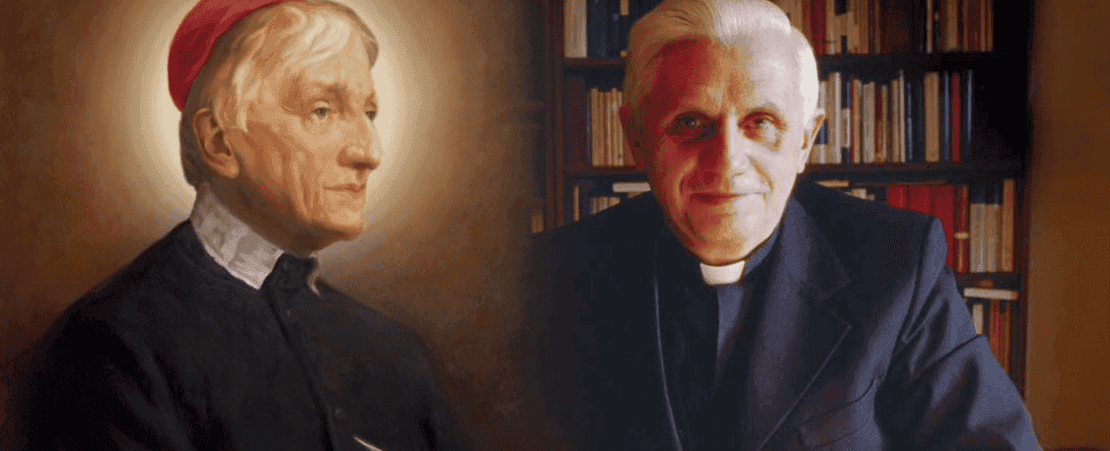

Newman, the Guide of Conscience for Ratzinger

On the final day of the year 2022, Pope Benedict XVI died at the age of 95. For decades he was regarded as the Catholic Church’s most profound theologian and now, after his death, remains one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century. When the Pope beatified Newman in 2010, he traveled to the United Kingdom to honor the “saintly Englishman” from whom he had learned numerous invaluable lessons. In his sermon for the occasion, the Pope exclaimed, “in Blessed John Henry, that tradition of gentle scholarship, deep human wisdom and profound love for the Lord has borne rich fruit.”

It is in this scholarly yet prayerful pursuit of the truth that Ratzinger found a fellow friend in Newman. Both as a scholar and as a Churchman, Joseph Ratzinger had a profound appreciation for St. John Henry Newman. As he wrote in his famous essay on Conscience and Truth, Ratzinger holds that Newman is the key element in developing a theory of conscience that distinguishes itself from modern relativism. In the modern sense, “conscience” is simply what a person thinks he should do. And modernity demands that he follows his conscience. But as Ratzinger, who grew up in Nazi Germany, poignantly notes, Nazis were convinced that they must follow what their conscience told them––what terrible repercussions this notion produced. The modern, subjectivist “conscience” as an “I have to do whatever I think I have to do” is destructive. “Liberalism’s idea of conscience,” Ratzinger argues, “[D]ispenses with truth. It thereby becomes the justification for subjectivity, which would not like to have itself called into question.” Calling on one’s conscience is then a retreat from the search for truth; it creates a “protective shell, into which man can escape and there hide from reality.” This ultimately leads to a dehumanization, since “man is reduced to his superficial conviction.”

Ratzinger’s conception of conscience, just as that of Newman, is rather different yet certainly more profound and far-reaching. Conscience properly understood is the inner voice of God. It is the opportunity to open our ears, hoping “that once again the promptings of God might be heard in human hearts.” It is not just an individual action, even though it is at first that conversation between a person and God. This Newmanian heart-to-heart conversation, which the Pope calls out in the beatification sermon as well, is infinitely valuable since it allows “the profound desire of the human heart to enter into intimate communion with the Heart of God.” Yet, conscience, if properly recognized and used, is also something communal: insofar as conscience is careful listening to God, and it becomes “a window through which one can see outward to that common truth which founds and sustains us all and so makes possible through the common recognition of truth the community of wants and responsibilities.”

For Ratzinger, Newman and Socrates are the prominent “guides to conscience.” Indeed, Ratzinger writes, Newman’s “life and work could be designated a single great commentary” on this question, tackled by the Anglican-turned-Catholic in a depth not seen in Church history since St. Augustine.

In his Conscience and Truth, the then-Cardinal masterfully lays out why Newman’s theory of conscience is essential. No, when Newman defends ‘conscience,’ he does not defend subjectivism and opposes the Pope––or even the Church, despite what his famous toast to conscience first and to the Pope second may sound like. Instead, between the individual subject and the external authority exists a “middle term,” which is truth, and can only be found by these two elements working together.

According to Ratzinger, Newman’s “conscience signifies the perceptible and demanding presence of the voice of truth in the subject himself.” It is truth and the voice of God that will guide us as persons. Yet, what is required to hear His voice is the overcoming of one’s own thinking so as to free the space for God to call us. “It is the overcoming of subjectivity in the encounter of the inferiority of man with the truth from God.” Ratzinger already sees Newman making this point very early in his life, when he writes in his famous poem The Pillar of the Cloud (Lead Kindly Light), “I loved to choose and see my path; but now lead thou me on!”

Thus, conscience is, at least at first, precisely not the mere following of one’s own desires and moods, but the abandonment of them and the surrender of our subjective thoughts and feelings to the truth––revealed to us by the voice of God. Eventually, by learning to listen to God’s voice, our desires will be reshaped and our personality expands by becoming greater disciples of Christ. Even so, Newman’s conversion was ultimately not “a matter of personal taste,” but an abandonment of this “personal taste” to God and His vehicle on earth, the Catholic Church.

Only in this sense can we, Ratzinger continues, “appreciate Newman’s toast first to conscience and then to the Pope.” For insofar as conscience is the existence and the perception of truth and of God, it always has to have primacy over both our individuality as well as external authorities. To the extent that we as persons or as an authority such as the Church violate truth, we do not follow conscience. The papacy is only legitimate when it follows the truths proclaimed throughout the Christian times, only insofar as the Pope is “the advocate of the Christian memory.” The Pope cannot “impose from without” but defends this very memory. “For this reason, the toast to conscience indeed must precede the toast to the Pope, because without conscience there would not be a papacy. All power that the papacy”––as a truth-defending office––“has is power of conscience,” that is, the perception and discovery of truth.

This listening to conscience, to the inner voice of God, will often lead to difficult decisions that both the Church and the individual person may have to make, even going against public perception. In this, Pope Benedict saw Newman fully in line with the martyrs of early Christianity as well as St. Thomas More. In surrendering his will to the truth, Newman attained “the holiness of a confessor” who suffered much not for his subjective convictions and feelings, but for his deep sense that what the much-despised Church proclaimed is the truth.

How did Newman arrive at this difficult conclusion of having to leave the Anglican church so as to become Catholic? Ratzinger praises many aspects of Newman’s life and work (which makes the Pope’s beatification sermon especially significant). Yet, what perhaps stands out the most is Newman’s commitment to prayer and to his service for his fellow Christians as a priest. Precisely in prayer was Newman able to hear God’s voice, precisely there was he able to “enter into intimate communion” with the Sacred Heart. Thus, “Newman reminds us that faithfulness to prayer gradually transforms us into the divine likeness.” And as Newman used the fruits of his contemplation and prayer life to develop a unique “intellectual legacy,” he also was drawn out into serving others in “his life as a priest, a pastor of souls.”

Thus, both Newman and Ratzinger shared key elements in their lives: both were fully committed to the truth, even in times of difficulties and personal challenges, both nourished themselves through their heart-to-heart conversation with Christ, and both eventually became apostles not just as intellectuals but also as pastors of their flock.

Share

Kai Weiss

Graduate Student in Theology

Kai Weiss is a graduate student in theology at the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, DC. He holds a MA in Politics from Hillsdale College and is a board member of the Hayek Institute. In spring 2023, he was a visiting scholar at NINS.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS