Newman's Visit to Rome in 1833: Part III

Part 3. Politics and Church Reform

Newman was interested in the events happening back home[1] and added that the church in England might console herself with the knowledge of having partners in misfortune in Sicily and Italy.[2] Years later, in his Apologia, he recalled what he truly felt: "England was in my thoughts solely, and the news from England came rarely and imperfectly. The Bill for the Suppression of the Irish Sees was in progress, and filled my mind. I had fierce thoughts against the Liberals."[3] He never wanted to remain neutral and was also confident of his Oxford friends' fidelity to the church: "Surely in bad times Oxford and its neighborhood will be the stronghold of the Church."[4] To defend the cause of the Apostolic Church, he began to talk about a new brotherhood, or even a club or society, and to recruit friends.[5]

Newman admitted frankly an absence of a comprehensive understanding of the principles and the "history of Church changes," and he realized "more and more the blunders one makes from acting on one's own partial view of a subject, having neither that comprehensive knowledge nor precedents for acting which history gives us."[6] He felt that the travelling was helping him to transcend his own particular station and decisions.[7] Certainly, in his correspondence, there were clear indications of his desire to participate in a movement aimed at the reform of the Church of England.

Newman's Reaction to Roman Catholic Churches and Institutions

Even in the midst of these preoccupations, Newman was eager to reach Rome by tracing the footsteps of St. Paul.[8] They reached Rome on Saturday, 2 March 1833. Two days later, he shared his impressions with his sister, Harriett:

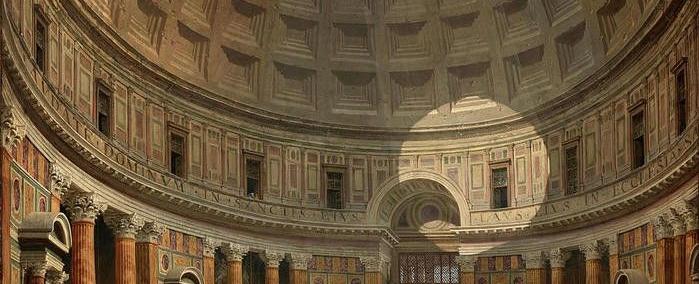

"And now what [can] I say of Rome, but that it is of all cities the first, and that all I ever saw are but as dust, even dear Oxford inclusive, compared with its majesty and glory. In St Peter's yesterday, and St John Lateran today, I have felt quite abased, chiefly by their enormous size, which added to the extreme accuracy and grace of their proportions makes one seem quite little and contemptible. The approach to Rome from Naples is very striking . . . Rome grows more wonderful everyday."[9]

Newman was at first fascinated with "the most delightful residences imaginable" in Rome.[10] Though he thought that he had experienced "none of that largeness and expansion of mind, which one of my friends privately told me I should get from travelling,"[11] he was "busily employed every morning in seeing sights, for, as Rome was not built, assuredly it is not to be seen, in a day."[12] He added: "It is the first city that I have been able to admire, and it has swallowed up, like Aaron's rod, all the admiration which, in the case of others, is often distributed among Naples, Valetta, and other places."[13] He summarized his feelings about the Eternal city in the line of Virgil: "Urbem, quam dicunt Romam, Melibœe, putavi, stultus ego!"[14]

With mixed feelings, Newman claimed that though he had not seen much, he could discern traces of long sorrow and humiliation, suffering, punishment and decay behind the vast and overpowering city of Rome.[15] His thoughts on Rome, however, swung from apocalyptic to religious and classical views.

An Apocalyptic Rome: Newman's mixed feelings about Rome were expressed in his essay, "Home Thoughts Abroad," that was later published in The British Magazine: "I was full of expectation and impatience for the sight of Rome; yet there was nothing here of promise to excite or gladden the mind."[16] Being in Rome for five weeks, Newman also described how Rome simultaneously delighted and terrified him.[17] Rome "is a very difficult place to speak of from the mixture of good and evil in it and the Christian system there is deplorably corrupt, yet the dust of the Apostles lies there, and the present clergy are their descendants."[18] In effect, "the spirit of old Rome" continued in the corrupt papal system of Christian Rome,[19] and he could not "quite divest himself of the notion that Roman Christian is somehow under an especial shade as Roman Pagan."[20] He thought that the spirit of the old Rome had risen again in its former place and was evidenced by its works.[21]

Newman's apocalyptic understanding of Rome had its basis not only in his reading of the books of Daniel and Revelation[22] but also in the writings of the fathers.[23] For him, it seemed that Rome would be "reserved for future super human judgments."[24] His thoughts about this apocalyptic fate of Rome seemingly haunted him as he was writing to Pusey and went into more detailed reflections on the basis of the Book of Revelation. He agreed with Thomas Scott's evangelical position that the last persecution was coming over the Christian world.[25] However, he was sympathetic to Rome by distinguishing between the sinner and the sin: "it does not follow that the Church [Church of Rome] is the woman of the Revelations, any more than a man possessed with a devil is the devil."[26]

He clearly made efforts to distance himself from any Protestant anti-Romanism. Further, Newman's observations would begin to provoke the Roman Catholic minds for ecclesial self-examination of their ritual and practices.

Classical Rome: Newman was amazed by the classical art-works he found in Rome, and they provided another view of Rome.[27] In "Home Thoughts Abroad," Newman remarked that Christian travelers, forgetting the Apocalyptic prediction on Rome, became "full of classical thoughts" and looked for "the footsteps of the Gracchi, and Brutus, and the philosophic Marcus."[28] Comparing Rome and Greece for their contribution in classics, he stated that the "Grecian genius is not cursed; and we may safely admire amid all its corruptions the fragments of a holier traditionary truth; but Rome is one of the 4 beasts,"[29] and there was "nothing classical except the Roman system."[30]

Religious Rome: The third view of Rome that Newman described in many of his writings during his journey was Rome as a place of religion in which pain and pleasure are mixed: "It is strange to be standing in the city of the apostles, and among the tombs of martyrs and saints."[31] In a letter to John Frederic Christie, he seemed to struggle again with a mixture of feelings: "Well then, again after this, you have to view Rome as a place of religion, and here what mingled feelings come upon one. You are in the place of martyrdom and burial of Apostles and Saints."[32] For him, "look on St Peter's and think that the Apostle was buried beneath, and think of St Paul too, and Ignatius and Laurence, and others whose names are in the book of life, who lie here in the dust, is enough occupation for the mind."[33]

As Newman traced out diligently and venerated piously the footsteps of apostles, bishops, and martyrs, he reminded his correspondents that a great many saints were buried there.[34] For him, the pride of place went to Pope Gregory the Great (590?604) because St. Gregory "has special claims on the respect of Englishmen, since he is the founder of our church."[35] Continuing his self-assumed role of pilgrimage?guide, he described a number of basilicas, churches, and catacombs, and commented on a picture of the Virgin of great antiquity.[36]

However, "the interest attendant on these, and similar memorials of the early Christians, vanishes before the enthusiasm which the traces of the great apostles, St. Peter and St. Paul excite in the mind."[37] Newman reminded his countrymen about the special meaning that St. Peter's should have for them. He acknowledged a number of "traces," or traditions such as the presence of St. Peter in Rome and the paucity of Petrine "vestiges" in Rome. Indeed, he was overwhelmed not only by the enormous size of St. Peter's Basilica, but also by its significance as the most magnificent church on "the foundation of the chief and representative of the apostles."[38] After defending the historical authenticity of Peter's presence in Rome, Newman discussed Peter's primacy among the apostles:

"And, next, take into account where this church is found; not in a distinct province of Christendom, but in its very centre, in Rome itself, the head of all, and the mother of many, of the churches of the West; nay, considering the state of Eastern Christianity, the enfeebled state of some of its churches, and the utter degradation of others, undeniably the most exalted church in the whole world."[39]

Newman then sought for an historical basis for Rome's exalted position.[40] Categorically, Newman's observations of the Petrine foundation of the primacy of the See of Rome provide a historical and ecclesiological viewpoint for the ecumenical discussion of the role of the See of Rome and her bishop, the Pope.

However, Newman was distressed to watch the court of Rome—perhaps the only religious court in the world. He could not endure watching "the Pope's foot being kissed" and "being carried in on high," "considering how much is said in Scripture about the necessity of him that is greatest being as the least."[41] He felt deeply the force of the parable of the wheat and tares as he was witnessing the customs and traditions of Rome.[42] In spite of this, he still felt more attached than ever to the Catholic system.

[1] Newman to Isaac Williams (Lazaret, Malta, 16 Jan 1833), LD iii: 198.

[2] Newman reported the miserable condition of the clergy and churches all through Italy and Sicily because of the interventions of politicians. See Newman to Frederic Rogers, (Rome 5 Mar 1833), LD iii: 234-35.

[3] John Henery Newman, Apologia, 22. See also Newman to Thomas Mozley (Rome, 9 Mar 1833), LD iii: 242; to Hugh James Rose (Rome 16 Mar 1833, LD iii: 252); to Henry Wilberforce (Rome, 9 Mar 1833, LD iii: 246-7); to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833) LD iii: 249; to R. F. Wilson (Rome, 18 Mar 1833), LD iii: 257-58 and to H. A. Woodgate (Naples, 17 Apr 1833), LD iii: 298. Newman's comments are thought-provoking in light of contemporary ecclesiological approaches such as those of Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, An Introduction to Ecclesiology (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2002), 8, who has spoken of "forms of churches", "Free churches" and churches that do not like to be called a "church." See also Newman to E. B. Pusey (Rome, 19 Mar 1833), LD iii: 259-62; to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833), LD iii: 250 and to Jemima Newman (Rome, 20 Mar 1833), LD iii: 264.

[4] Newman to Walter John Trower (Naples, 16 Apr 1833), LD iii: 293.

[5] Newman to H. A. Woodgate (Naples, 17 Apr 1833), LD iii: 300.

[6] Newman to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833) LD iii: 249.

[7] Absence of a comprehensive ecclesiology and an awareness of the importance of tradition and precedence in ecclesial praxis among Newman's collogues is reflected in his observations. See Newman to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833) LD iii: 249.

[8] Newman to Mrs. Newman (Malta, 26 Jan 1833), LD iii: 206.

[9] Newman to Harriett Newman (Rome, 4 Mar 1833), LD iii: 230-31.

[10] Newman to R. F. Wilson (Rome, 18 Mar 1833), LD iii: 258:

[11] Newman to Thomas Mozley (Rome, 9 Mar 1833), LD iii: 242.

[12] Newman to Thomas Mozley (Rome, 9 Mar 1833), LD iii: 242.

[13] Newman to Frederic Rogers (Rome, 5 Mar 1833), LD iii: 233-34.

[14] Newman to Frederic Rogers (Rome, 5 Mar 1833), LD iii: 233-34. In Virgil's first Eclogue, Tityrus addressed Melibœus: "Melibœus, I foolishly thought that the city they call Rome was like ours."

[15] Newman to Frederic Rogers (Rome, 5 Mar 1833), LD iii: 233-34.

[16] See Newman's "Home Thoughts Abroad," The British Magazine, and Monthly Register of Religious and Ecclesiastical Information, Parochial History, and Documents Respecting the State of the Poor, Progress of Education, &c. (London: J. G. & F. Rivington) Vol. V (1 Jan, 1834): 1-11. The second part of "Home Thoughts Abroad. – No. I" appeared a month later (1 Feb, 1834):121-31; copies of the first two parts of "Home Thoughts Abroad" (abbr. "Thoughts") were generously provided by Dr. Mitzi Budde, Bishop Payne Library, Virginia Theological Seminary.

[17] Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 287. See also the second part of "Thoughts. – No. I" The British Magazine Vol. V (1 Feb, 1834): 121-31, at 123.

[18] "Thoughts", 123.

[19] "In the corrupt papal system, we have the very cruelty, the craft, and the ambition of the Republic; . . .Old Rome is still alive." "Thoughts", 123.

[20] Newman to R. F. Wilson (Rome, 18 Mar 1833), LD iii: 258. The notion—both evangelical and apocalyptic—of Rome surfaced in many of Newman's letters; see Newman to John Frederic Christie (Rome, 7 Mar 1833), LD iii: 240; to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833) LD iii: 248-49; to Harriett Newman (Rome, 4 Mar 1833), LD iii: 231. "Thoughts," 2.

[21] Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 288-89.

[22] Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 287.

[23] "Gregory the Great seems to have held the notion (3 centuries after Rome became Christian) that still the spot was accursed." Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 287-78.

[24] "That this doctrine evidently has been acknowledged by a considerable party in the Church, and as a tradition has a sort of authority of the opinion of the Church." Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 288.

[25] Newman to E. B. Pusey (Rome, 19 Mar 1833), LD iii: 259-62 and also Newman, "Thoughts," 123-24.

[26] Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 288.

[27] Newman wrote to Harriett Newman (Rome, 4 Mar 1833) LD iii: 231-32: "Next when you enter the Museum etc, a fresh world is opened to you, that of imagination and taste. You have there collected all the various creations of Grecian genius, the rooms are endless, and the marbles and mosaics so astonishingly costly. The Apollo is quite unlike his casts. And the celebrated pictures of Raffaelle! They are above praise, such expression! What struck me most was the strange simplicity of countenance which he has the gift to bestow on his faces." Three days later, Newman shared the same view of Rome with John Frederic Christie (Rome, 7 Mar 1833), LD iii: 240.

[28] "Thoughts," 7.

[29] Newman to George Ryder (Rome, 14 Mar 1833), LD iii: 249.

[30] "Thoughts," 2.

[31] Newman to Harriett Newman (Rome, 4 Mar 1833), LD iii: 232.

[32] Newman to John Frederic Christie (Rome, 7 Mar 1833), LD iii: 240-41.

[33] Newman to Jemima Newman (Rome, 20 Mar 1833), LD iii: 263. See also "Thoughts," 8.

[34] For Newman: "The most eminent of these are, of course, St. Peter and St. Paul, both of whom lie buried here; then St. Clement, St. Sebastian, St. Laurence, St. Dionysius, and St. Gregory" ("Thoughts," 8). See also Newman to Samuel Rickards (Naples, 14 Apr 1833), LD iii: 290.

[35] In 596, Pope Gregory sent Augustine, the prior of the monastery that Gregory had founded on the Cœlian Hill, to England as the head of a missionary band. See "Thoughts," 8, and also Newman to Harriett Newman (Rome, 4 Mar 1833), LD iii: 232.

[36] "Thoughts," 10-11.

[37] "Thoughts" 11.

[38] Newman was more inclined to accept the three traditional locations: St. Peter's residence, the site of his martyrdom, and the place of his burial. "Thoughts," 121-22.

[39] "Thoughts," 121-22.

[40] "Thoughts," 122-23: "From the first, it was known and respected throughout Christendom for the dignity and wisdom of its conduct. The name of Peter is typical of the church which he governed, as denoting its steadfast and determinate position amid the waves of heresy by which Christianity was assailed. The unstable Greeks took refuge in the decisions of the clear-sighted and manly Latins. Nay, the greatest prelates of other countries, the apostolical Cyprian, the large-minded Dionysius, and the richly-gifted Athanasius were corrected or supported by the see of Rome."

[41] Newman to Mrs. Newman (Rome, 25 Mar 1833), LD iii: 268. In Newman's time, papal protocol required that visitors kiss the pope's foot; until 1978, the pope was carried to and from ceremonies by attendants in a portable throne (sedia gestatoria).

[42] Newman added: "Indeed the more I have seen of Rome the more wonderful I have thought that parable, as if it had a directly prophetic character which was fulfilled in the Papacy" (Newman to Samuel Rickards, Naples, 14 Apr 1833, LD iii: 289).

Share

Fr. Joseph Elamparayil

Independent Scholar, Catholic University of America

Fr. Joseph Elamparayil is a graduate of The Catholic University of America. His dissertation is titled, "John Henry Newman's Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church: A Contextual History and Ecclesiological Analysis."

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS