Newman’s Ecology of Ascesis

“Nothing is so likely to corrupt our heart, and to seduce us from God, as to surround ourselves with comforts,—to have things our own way,—to be the centre of a sort of world, whether of things animate or inanimate, which minister to us.”

- John Henry Newman, “The Duty of Self-Denial”

Newman’s description of self-denial in light of the invisible world can help us to examine and renew three fundamental relationships: with God, our neighbor, and the natural world. Two of his Parochial and Plain Sermons are particularly helpful for our understanding of these relationships. Newman’s engagement with the idea of ascesis (discipline) in “The Duty of Self-denial” and his theology of the correlation of the visible and invisible realms in “The Invisible World” are particularly helpful for our task of ordering our relationships in a way that supports the integral vision proposed here. Similarly, Newman’s theology helps us navigate a set of practices that cultivate the fundamental relationships of Christian life.

The Duty of Self-denial

Newman preached “The Duty of Self-denial” in March 1830, halfway through Lent. He sets out a classic version of Christian discipline: “The Christian denies himself in things lawful because he is aware of his own weakness and liability to sin.” He asserts that self-denial is uncommon both in general and with people who profess to be religious. He also demonstrates that Scripture—both Old and New Testaments—commands self-denial, and adduces practical reasons that self-denial is necessary for a Christian life. Most strikingly, Newman sets out what one might call an ecology of ascesis (ecology: the logos “order” of oikos “home, household”), in which discipline must help to reorder our lives and relationships, dethroning us from the center our own world. Newman argues for practices that draw us out from ourselves into praise of God and service of neighbor.

In the second sentence Newman speaks of “things we do not naturally love” and of “natural wishes.” He refers to the “warfare of faith against our corrupt natural will.” He explains that “we naturally love the world, and innocently,” but that we must be weaned from natural loves to love higher things above all. Much of the sermon focuses on the difficulty of turning from natural to higher loves, but at the end Newman pivots. In his last sentence he states that through practice “self-denial [shall] become natural to you.” Much like a musician who practices a piece until it becomes “second nature,” it is through right intention and repeated practice that even what is hard can become easy, or “natural.”

From this discussion of how the difficult can become natural, Newman turns his discussion to the heavenly. In the Christian life, our practice of virtue is rooted in our repeatedly imitating Christ. In reference to St. Paul, Newman writes, for example: “Nor let us think it over-difficult to imitate him … If we would be followers of the great Apostle, let us fix our eyes upon Christ our Saviour; consider the splendour and glory of His holiness, and try to love it.”

Inherent in imitating Christ is the practice of self-denial. Self-denial enables us to love our friends and family (our neighbors) truly, wanting their ultimate good, not just what we might superficially desire to give them or seek from them. Self-denial keeps us from letting others’ praise or blame knock us off course. For Newman, continually gazing on Christ is what can make the arduous good of self-denial into something lovable and even natural.

The Invisible World

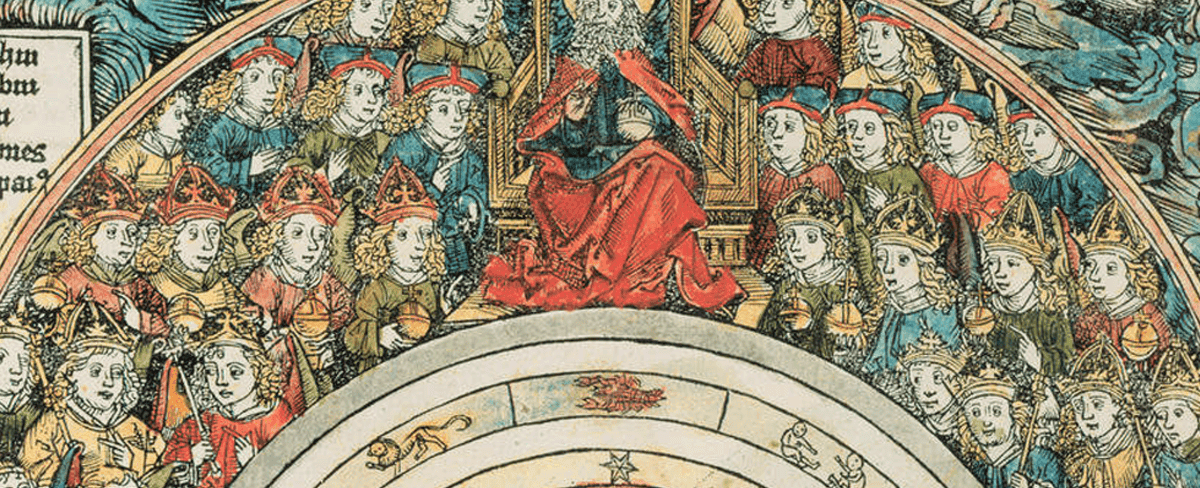

In his sermon, “The Invisible World” (July 1837), Newman’s reflects on the relationship between the “natural” world and the divine world. According to Newman, the natural, or material, world points to the very real invisible, or divine, world. In this life we are always participating in both worlds. “We are in a world of spirits, as well as in a world of sense,” he says. Though unseen, there is an invisible world—of God, the souls of the dead, and angels—even nearer to us than what we see in the visible world.

Newman explains that these two worlds—invisible and visible—exist alongside one another, though we are only able to experience the invisible occasionally when the divine world breaks forth into our world of the senses. What ties these two worlds together for Newman is the sacramental imagination. We, though living in the visible world, participate in the divine world and experience it in a real way in practice of Christianity, particularly in our participation in the sacramental life of the church. Newman demonstrates this relationship between the two worlds in his analogy of the season of spring as an image of the invisible world’s bursting forth when the visible world passes away. Newman’s reflection on the relationship between the visible and invisible world can help us navigate our relationships both with one another and with the natural world. Too often it is easy to focus on one sense of nature to the detriment of the other. It is important to remember that human nature and the natural world are part of one order, created by the “maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.”

Though Newman is primarily interested in demonstrating the reality of the invisible world to his Victorian congregation, one may draw some contemporary conclusions about our relationship with the natural world. In this sermon, Newman emphasizes that we should not think of ourselves as the center of any world, visible or invisible. The invisible’s nearness to us relativizes what is visible, sets it in context. The reality of the invisible world frees us from straining to make ourselves “the centre of a sort of world.” This point opens a possible application of Newman’s intuition to a contemporary issue concerning our treatment of the natural world.

Often our culture is—or claims to be—materialist, in that we focus our sights only on the world of the senses, what Newman calls the visible world. Human beings, though, as Newman demonstrates in this sermon, ought to desire sight of the invisible through our participation in the visible. To put it another way, this world of the senses cannot fulfill us completely; it is only in the divine world that we experience our human nature in its fullest.

Our increasingly unfulfilled desire for the material revolts by digging in, searching hopelessly for fulfillment in the finite. It may double down on demanding and purchasing, hoping that infinite action will sate infinite desire, a kind of existential shopping addiction. We can bring this struggle to our approach to human nature, as Newman seems to understand human nature. We can view our bodies and souls as something to bend to our demands, instead of good in themselves. When use the material world to try to sate our predicament, we demand of matter what it cannot provide.

If Newman is right, there is hope for us. Newman’s sermon expresses the hope that there is an invisible world, spiritual and utterly near to us, in which we can participate sacramentally now with the hope of full sight in the eschaton.

Conclusion

In both sermons Newman points to God’s goodness by speaking about the Incarnation, both directly and indirectly. He writes that “spontaneous and exuberant self-denial” brought God down in the flesh, and it is in Christ that the visible and invisible worlds converge.

Newman invokes spring as an image of how the invisible world breaks forth into our current state and sanctifies our vision. We might also seek in it an image of Christ’s self-denial. In the bloom of spring, we see the seed that falls to the ground and bears much fruit.

Christina Rossetti, who knew Newman’s work and owned some of his books, sums it up in her poem “Spring”:

There is no time like Spring,

Like Spring that passes by;

There is no life like Spring-life born to die,—

Piercing the sod,

Clothing the uncouth clod,

Hatched in the nest,

Fledged on the windy bough,

Strong on the wing:

There is no time like Spring that passes by,

Now newly born, and now

Hastening to die.

Share

Samuel Bellafiore

Priest, Diocese of Albany, NY

Fr. Samuel Bellafiore is a priest of the Diocese of Albany, New York.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS