Newman and Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius

Not all those familiar with St John Henry Newman’s evocative poem, The Dream of Gerontius, will be acquainted with its musical setting by the English composer Edward Elgar. Composed in 1900, a decade after the Cardinal’s death, Elgar’s Gerontius is not a collaboration but a new interpretation. What, then, did Newman’s poem mean to Elgar, and how did the composer articulate Newman’s vision musically?

Elgar was born in 1857 in the village of Lower Broadheath, Worcestershire. His background and upbringing were very different from Newman’s. Elgar’s mother Ann converted to Catholicism before his birth, and the composer was raised Roman Catholic and worshipped at St George’s Chapel, Worcester, where his father was organist for many years. The Elgars were lower-middle class, running a music shop on Worcester High Street. In his later life as national composer, Sir Edward Elgar continued to be shaped by his consciousness of his humble, provincial, Catholic origins.

Elgar became acquainted with Newman’s poem years before embarking on his musical setting. The poem had generated considerable interest in England when, in 1885, news was circulated that General Charles George Gordon had a copy on him when he was killed in the Sudan. Considered a martyr at the time in imperial Britain, Gordon was a heroic figure and his pencil markings of key passages in the poem were widely copied. Elgar himself received a copy of the poem with these inscriptions as a wedding present in 1889. Ten years later, he was strongly considering writing a ‘Gordon’ symphony capturing the General’s ‘martial achievements, restless energy, and religious fervour’ for the famous Three Choirs Festival, but abandoned the project.[1]

Elgar’s setting of Gerontius eventually happened in the context of a commission for the 1900 Birmingham Music Festival, of which Newman himself had been a vice-president. There had been previous efforts to interest composers in setting Newman’s poem—Dvo?ák was invited to do so in 1888—but without success.[2] Once he had established permission from both the Festival committee and the Birmingham Oratory, Elgar set about composing the work, mainly at his writing retreat of Birchwood Lodge, near Malvern. The composer showed a marked respect for the poem, only shortening Part 2 to a length more appropriate for musical setting, and resisting suggestions that he alter the text in any way in response to Protestant unease at the explicitly Catholic treatment of Mary, Mother of God, the rite of extreme unction, and the doctrine of Purgatory. Nevertheless, the work is very far from a conventional sacred work. Elgar wrote to his friend August Jaeger:

I imagined Gerontius to be a man like us, not a Priest or a Saint, but a sinner, a repentant one of course but still no end of a worldly man in his life, & now brought to book. Therefore I’ve not filled his part with Church tunes & rubbish but a good, healthy full-blooded romantic, remembered worldliness, so to speak. It is, I imagine, much more difficult to tear one’s self away from a well to do world than from a cloister.[3]

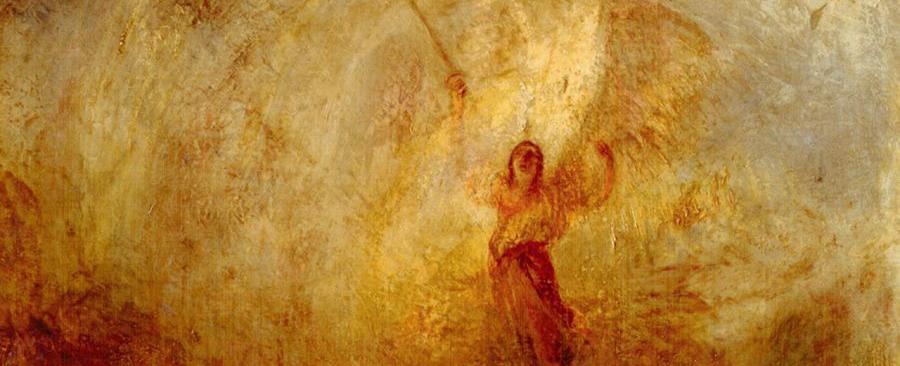

As we can see from this quotation, Elgar consciously avoided a sacred style other than in specific moments of the work. Rather, the overall musical language is Wagnerian – at the time, the most modern musical language available. Moreover, by this account, the heroic and martial themes that might have inspired a ‘Gordon’ symphony are gone; Elgar’s Gerontius is an Everyman, one deeply connected to the world and carrying it with him in memory beyond. This interpretation chimes closely with Newman’s depiction of the Soul hearing music but then remarking ‘I cannot of that music rightly say/Whether I hear, or touch, or taste the tones’. For both Newman and Elgar, the experience of the world was fundamentally sensual. There is a further connection between the journey of the restless soul and sensual experience common to poet and composer. Newman wrote, famously, ‘The sound is like the rushing of the wind – /The summer wind—among the lofty pines’. Matthew Riley has underscored the connections here with English poetry in which the rustling wind signifies spiritual awakening.[4] For Elgar, there was an added personal connection to his love of the Worcestershire countryside and particularly the fir trees at his birthplace cottage, his school Spetchley Park, and Birchwood Lodge. Indeed, the manuscript of Gerontius is peppered with remarks on Birchwood in summer or during thunderstorms, reinforcing the connection (click below to view document, page 167).

At the time of its creation, Elgar’s work encountered several difficulties. The first performance in Birmingham was a notorious disaster due to personnel change and under-rehearsal of the difficult score. While subsequent German performances were a great success, prompting Richard Strauss to anoint Elgar as a modern composer of international stature, the leading British composer Charles Villiers Stanford suggested it ‘stank of incense’, and the text had to be bowdlerised before the music could be performed in the Anglican Worcester Cathedral. These objections are especially interesting, given that settings of the Mass and works in Latin had previously been performed in Anglican churches. Perhaps it was not only references to doctrine that offended the clergy of Worcester, but the most striking aspect of the musical-poetic work: its visceral sense of the soul’s longing for God, expressed in a passionate, immediate, and indeed sensual musical language.

[1] Cited in Percy M. Young, Elgar, Newman and the Dream of Gerontius: In the Tradition of English Catholicism (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995), 112.

[2] Young, Elgar, Newman and the Dream of Gerontius, 101.

[3] Jerrold Northrop Moore (ed.), Elgar and his Publishers: Letters of a Creative Life (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 228 (italics original).

[4] Matthew Riley, Edward Elgar and the Nostalgic Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 93.

Joanna Bullivant

Departmental Lecturer in Historical Musicology at the University of Oxford

Joanna Bullivant is Departmental Lecturer in Historical Musicology at the University of Oxford, having previously held appointments at the University of Nottingham and King’s College London. She has published widely on the history of British music in the twentieth century, with particular emphasis on intersections of music with politics and social history. She is also a digital musicologist. Her current research situates Edward Elgar’s music in the context of nineteenth-century English Catholicism.

QUICK LINKS