Lost Voices of the Catholic Literary Revival

In the English-speaking world, the Catholic Literary Revival is associated with the work of G. K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, and Graham Greene: novels that chart the solitary figure of a priest or layman in spiritual combat with the world around him. The Revival is usually seen as concentrated in the south of England from around 1900 to 1960. But in fact, the Revival’s most numerous members were women, many of whom have been almost entirely forgotten. When these women are put back in the frame we need to adjust our understanding of the Revival’s nature and scope.

Catholic Women Writers is a recent series with the Catholic University of America Press that brings back into print novels and short stories by forgotten Catholic women from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The work of these women indicates that the Revival lasted much longer than is usually thought (women were writing earlier and later than most of the men associated with the Revival) and that its writers were located in all areas of Britain and Ireland, not merely in the south of England. Novels by Catholic women are often concerned with different theological questions than we find in the work of Waugh and Greene. They are set in families and villages and in the institutional communities in which the writers themselves first encountered the faith: schools, convents, or convent schools. Almost wholly unrecognized by scholarship of the Catholic novel, or indeed the novel generally, are the frequent depictions of female religious life in novels of the twentieth century.

One of the Revival’s greatest literary treasures is Josephine Ward, who lived between 1864–1932. She and her husband, Wilfrid Ward (biographer of Newman and others), had close ties with Newman and Manning, Tennyson and Huxley, Gladstone, Benson and Belloc, the von Hügels and the Chestertons. She wrote ten novels, theological pamphlets, and articles for the Dublin Review and The Spectator. She raised five children, one of whom, Maisie Ward, went on to found the largest and most prolific modern Catholic publishing House (Sheed and Ward).

In their writing, Josephine and Wilfrid were both concerned with the question of how to realize the fullness of human character in prose: What is a person? How is character formed? Josephine wrote in the Dublin Review that “the greatest drama is the unfolding of the action of the will as it adheres to or thwarts the Divine purpose.” But as a life-long friend of Newman’s, she was also steeped in his ideas about conscience and the formation of moral character, as well as about the importance of doctrine for both. Another central concern of Josephine’s—as topical today as it was then—was how to enable her children to participate in the best of public, intellectual, and cultural life, without exposing them over-much to the influence of institutions that remained fundamentally opposed to Catholic belief and practice.

All of these problems are explored in Ward’s first novel One Poor Scruple. It examines the social reality of English Catholics in and around London in the 1890s: Will they be able to use their conscience well when set loose in fashionable society? The novel’s protagonist is Madge, a young widow and a lukewarm Catholic highly attracted to worldly pleasures and societal prestige. When Madge receives an offer of marriage by the rich and handsome Lord Bellasis, she seems to have it all. Bellasis is a divorcee, however, and hence, in the eyes of the Church, technically still married. To her own and others’ surprise, this gives rise in her to just “one poor scruple” about her marriage plans. The novel uses the classic romance narrative, with its pattern of a protagonist struggling to find love and happiness amid an array of choices. But it uses it to explore the tension between romantic desires and religious truth and hence the significant degree of personal sacrifice that religious faith may demand of a person. Strikingly, Ward—like other female writers of the Revival—allows a Catholic doctrine to inform the inner experience and actions of her characters, such that doctrine becomes central to the novel’s plot development and, by implication, to reality itself.

Another great writer using the most up to date narrative techniques for specifically Catholic purposes is Caryll Houselander. Her 1947 novel The Dry Wood charts the nine days of a novena in Riverside, a London docklands parish praying for the life of one of its most vulnerable members, the disabled boy Willie Jewel. Houselander innovatively transforms modernist experimentation with time, place, and multi-vocalism. In effect, these techniques manifest not the lack of human connection in the modern world (as they would in the works of Virginia Woolf, for instance) but, instead, the deep, unfelt and unseen work that binds people through Christ. Throughout the novel, the reader is given the opportunity to see things with both human and divine eyes, thereby challenging preconceived or assumed notions of what is real.

Another writer of the Revival now back in print in the Catholic Women Writers series is Sheila Kaye-Smith, until recently forgotten but a bestseller in the 1920s. Her 1925 novel The End of the House of Alard was written during her conversion from high Anglicanism to Catholicism and, long before Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, explores the post-war erosion of the aristocracy from a Catholic point of view. Faced with the decline of their family estate, Alard’s characters must discern between intrinsic and instrumental goods. In relaying their struggles, Kaye-Smith boldly takes all that was most loved about her own best-selling genre—the aristocracy’s glamour, its age-old traditions, and its role in community-building—and subordinates it to a higher truth. The novel in some ways dramatizes Kaye-Smith’s own experience of how many fruits of the world can, and at times must, be put aside by those who choose God, and how this sacrifice brings with it different riches entirely unseen and unknown by those who refuse to give up what is most dear to them.

This emphasis on the potential cost of religious faith goes hand in hand with a sense of the meaning of human suffering. As women, many writers of the Revival knew what it meant to live on the margins of society: many of them, such as Josephine Ward and Mary Beckett, were writing alongside running households and raising large families; Caryll Houselander was a mystic and an artist who struggled to make ends meet and who spent much of her time ministering to neurotics and other lost souls; Sheila Kaye-Smith and her vicar husband lost their entire social circle and livelihood when they joined the Catholic Church; and Enid Dinnis was a “hidden nun” whose order engaged in a quiet and inconspicuous form of apostolate.

Yet, their writings have a light touch. They are hopeful and empathetic and, at times, humorously depict the more absurd manifestations of religious practice. Their joyful note can be explained with regards to their incarnational spirituality and sacramental outlook. In keeping perhaps with the more material and bodily nature of female existence, all of these women are deeply conscious of an unseen world behind material phenomena. In The Dry Wood, Houselander dramatically and movingly enacts her conviction that Christ’s life and passion continues in human lives today: Willie Jewel is clearly a Christ-figure surrounded by Mary and Joseph, by Mary Magdalene and Pontius Pilate. Even the less explicitly spiritual novels of the Revival share this theme of encounter Christ in the labors of everyday life. Irish writer Mary Beckett’s Troubles novel Give Them Stones, out in this series later this year, charts the story of Martha Murtagh, a Catholic home baker trying to support her family amid mounting political violence. Here too it becomes clear that biblical history, in a sense, continues in mid-century Belfast when Martha is able to encounter the transcendent God in the simple labour of kneading bread. In Alard, too, different characters, such as Stella and Gervaise gradually approach God through completing simple menial tasks like preparing medicines and filling them into bottles or working in a garage as a car mechanic. In Dinnis’s short stories, the world is enchanted in the manner along the lines proclaimed by G. K. Chesterton, and it is redeemed through the simple heroism of children and fools.

The work of the women writers of the Revival challenges readers to see religious faith as real and as a concrete force in human life and experience. It finds a natural and authentic place in the novel form. The forgotten work of women writers enacts and helps to form the Catholic imagination by challenging our rehearsed ways of seeing the world and by inviting a deeper vision of it.

This event was co-sponsored by NINS and by The Lumen Christi Institute.

Share

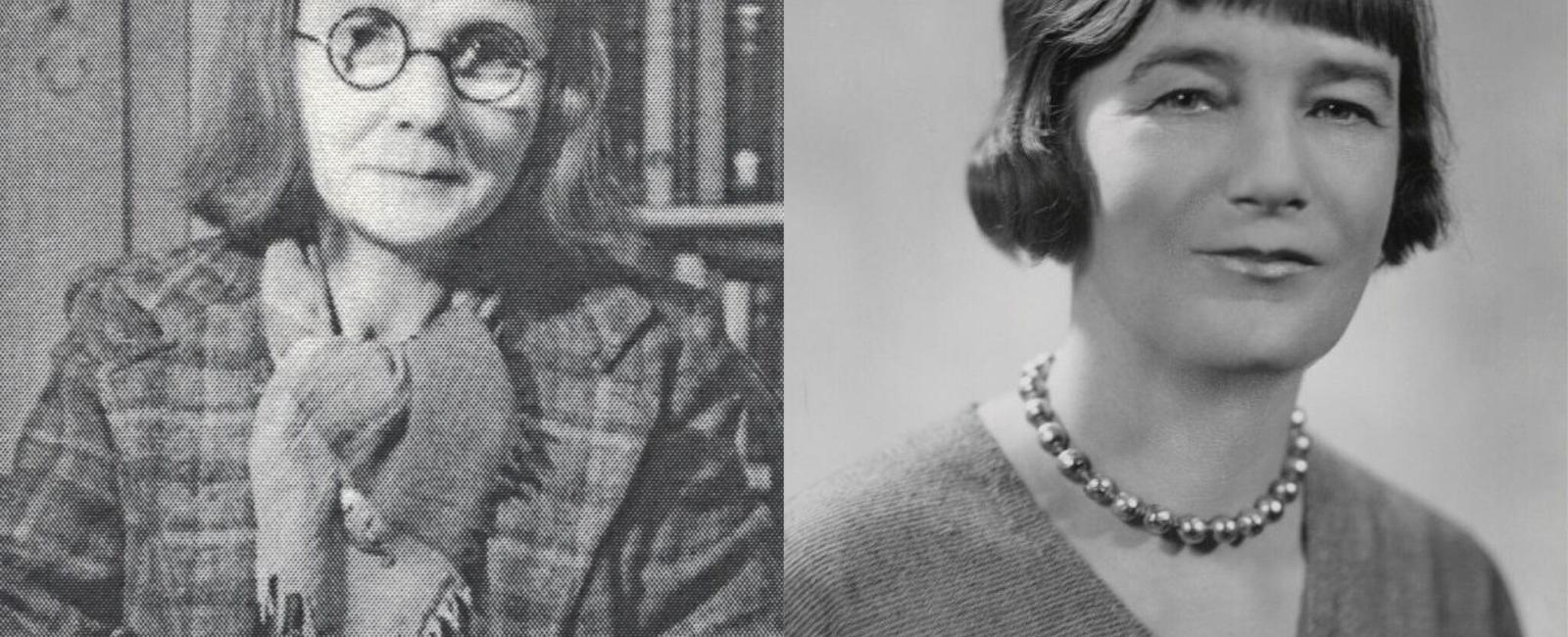

Bonnie Lander Johnson

Bonnie Lander Johnson is Fellow and Associate Professor at Downing College, Cambridge University. She writes fiction, non-fiction and academic books about Shakespeare and Renaissance literature. With Julia Meszaros she edits the CUAP series Catholic Women Writers.

Julia Meszaros

Julia Meszaros teaches systematic theology at St Patrick's Pontifical University, Maynooth (Ireland). She publishes in the areas of theology and literature and of theological anthropology, with a special focus on sacrifice and love. With Bonnie Lander Johnson she edits Catholic Women Writers, the CUA press multi-volume series of novels by women of the Catholic Literary Revival.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS