John Henry Newman's Pandemic Ministry: A Balm for the Bereaved

John Henry Newman’s condolence letters had a profound effect on the widow of Rev. Walter Mayer. She describes how his words “poured balm into the wounded mind,”[1] as did his funeral homily. Upon re-reading it in the evening, she told Newman: “I seemed to be raised far above things of time and sense. I forgot I was a mourner.”[2] This article explores how Newman’s correspondence and sermons can continue to bring consolation in the circumstances of Covid-19 when viewed in light of his own pandemic ministry. Newman lived through four major cholera outbreaks: 1831–1832 (21,800 deaths), 1848–1849 (53,292 deaths), 1853–1854 (20,097 deaths), and 1866 (14,378 deaths). These four outbreaks thus involved the loss of more than 100,000 men, women, and children.[3]

Newman draws Richard Froude’s attention to a case of cholera that was located in Rev. Samuel Rickards’s parish.[4] It was found near a port where a coal barge carrying infected sailors had docked, but not quarantined, as the government had ordered ships to do in October of 1831. Until the mid-1850s the disease itself was thought to be spread by bad smells or contagion, rather than contaminated water supplies. In his own pastoral setting of Littlemore, Newman wrote a specific Memorandum about the Cholera (revised in 1857 and again in 1874). This memorandum charts both the presence of cholera and Newman’s absence for reasons of work and recuperation. He notes that when he heard of a person with suspected (or actual) cholera, he “went at once to the house where the suspicion lay.”[5] He also records an instance where he was of two minds whether to return to his parish base when the disease was circulating outside the church boundaries. This is because, as he explains to Henry Wilberforce: “It would greave me much did a case occur when I was away.”[6]

During the first pandemic, his sister Jemima—anxious for his safety—recounts the rumour in Oxford that thirteen out of fifteen university servants (or Scouts) died as the result of contaminated soup, which was left out all night after the Magdalen College annual Gaudy celebration.[7] A month later, Newman tells Samuel Wood that “the cholera has made a second or third start in Oxford.”[8] He notes a few weeks later in his diary that it appeared to have run its course and that he was planning a thanksgiving service with the Archdeacon.[9] Later in his life, as a Catholic priest, he said “anti-cholera” masses and led benedictions for its demise.

Newman never forgot being part of the thirteen parishes under the Oxford Board of Health, which, in 1832, had 174 cases of cholera with 96 deaths—25 of which were children. One article refers to the sick as having been “attacked without distinction.”[10] This is a chilling reminder that which is echoed in some of the narratives surrounding Covid-19 that describe it as a war. Newman also draws military analogies when commenting about his own grief. In the midst of coping with the death of his community doctor and the critical illness of a friend, he confides to Anne Mozley that it is like being “in a hail of bullets.”[11] Similarly, to James Hope-Scott, Newman writes: “The March of time is very solemn now—the year seems strewn with losses—and to hear from you is like hearing the voice of a friend on a field of battle.”[12] Newman also acknowledges to Miss Mary Holmes the fear that can result from sudden deaths: “In the last few months three either sudden or unexpected deaths have fallen upon us in our intimate circle, and quite scared us.”[13] His words to Edward Badeley are apposite in the context of the pain of death and the restrictions upon human intimacy that social distance brings. Newman writes:

“There is something awful in the silent restless sweep of time—and, as years go on, and friends are taken away, one draws the thought of those who remain about one, as in cold weather one buttons up great coats and capes for protection.”[14]

Amid the cholera outbreak in 1832, Newman preached his somber-toned sermon, The Lapse of Time. He emphasizes the fragility of life, certainty of death, and trauma of bereavement, as well as the need for conversion amid the reality of God’s merciful judgment:

“Those whom Christ saves are they who at once attempt to save themselves, yet despair of saving themselves; who aim to do all, and confess they do nought; who are all love, and all fear; who are the most holy, and yet confess themselves the most sinful; who ever seek to please Him, yet feel they never can; who are full of good works, yet of works of penance. All this seems a contradiction to the natural man, but it is not so to those whom Christ enlightens. They understand in proportion to the illumination, that it is possible to work out their salvation, yet to have it wrought out for them, to fear and tremble at the thought of judgment, yet to rejoice always in the Lord, and hope and pray for His coming.”[15]

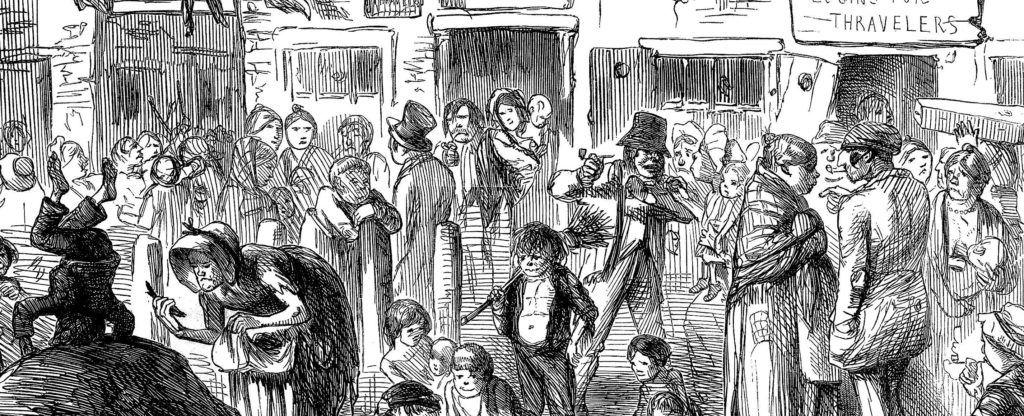

Caring for the poor, who were the ones most affected by cholera, became a major priority for Newman. He was conscious of their spiritual, practical, and social needs. He provided coal for heating, secured employment opportunities through his contacts, and paid their bills, despite being financially stretched himself. He recognized their need to relieve stress, and he robustly defended their dignity to Charles Golightly after it was undermined by the Temperance Society. He dismissed their crude, blanket characterization of the poor as “drunkards” by saying this view “during the prevalence of the cholera was very presumptuous and hard-hearted.”[16] Throughout September, he played the violin to relax, and a few weeks after, on 29 October 1832, his diary states that he “buried early porter of All Souls, suspected to have died of cholera.”[17] He also refers to another favorite hobby of his to his Aunt Elizabeth in 1842:

“What a dream, to be sure, that coming of cholera is! How it threatened, and how it went away! The most mysterious circumstance is that it was not overcome. It was not that medical science met and foiled it: but after showing its invincible powers, it retired in triumph, as mysteriously as it came.” At the end of his wide-ranging and conversational letter, Newman remarks, “I am reading Lockhart’s Life of Scott for recreation.”[18]

Newman’s understanding of how to strengthen people’s faith, hope, and love in the face of an epidemic developed as well. A short time after remarking in 1832 to Richard Hurrell Froude that, as well as the Asiatic strain, “there is much English cholera about,”[19] Newman delivers a sermon entitled On justification by faith alone. A decade later, on the cusp of a fresh wave of infections, he enhances the conclusion of The Lapse of Time:

“It is not merely a state of grace in which Christ puts us, He puts grace into our hearts. He is not merely around us but in us. He not only accounts us righteous but He makes us so. He enters into us with that righteousness of which He is Himself the fullness. He enters into our hearts, our thoughts, our affections, our aims, our exertions. He enlarged our faith. He deepens our repentance, He inflames our love, He strengthens our obedience, He beautifies and perfects our holiness.”[20]

Newman focuses his attention on the paschal mystery when comforting the bereaved. He consoled Mrs. Higgins in her loss by saying: “desolation, the word we use in Holy Week for the special anguish of the Blessed Mary, is the only word which touches the case of one who lives under the weight of your special affliction.”[21] Similarly, writing to Mrs. Froude about the death of her son Arthur, he observes: “This is a sorrowful Easter day for you—yet a joyful one too. Through the past week you have been like the Blessed Virgin under the cross.”[22] As well as being infused with the reality of risen life, Newman was mindful of the intense suffering that grief brings. In his sermon Affliction, a School of Comfort, he crystalizes his thought. By permitting the loss of a loved one:

“God … brings [those who greave] into pain, that they may be like what Christ was, and may be led to think of Him, not of themselves. He brings them into trouble, that they may be near Him. When they mourn, they are more intimately in His presence than they are at any other time. Bodily pain, anxiety, bereavement, distress, are to them His forerunners. It is a solemn thing, while it is a privilege, to look upon those whom He thus visits.”[23]

Uniting himself with the sufferings of Christ, and inviting others to do the same, remained for Newman an ongoing journey, especially concerning his youngest sister Mary and his Oratorian confrère Ambrose St. John. As Louis Bouyer perceptively asks in Newman’s Life and Spirituality: “If the wound remains open does it not become the glorious stigmata on the body of the Risen Saviour?”[24]

Sorting through the personal possessions of family, friends, or relatives is especially difficult. Newman empathized with Lord Kerr’s task: “it is like a second death.”[25] He admitted to Harriet that opening a box and seeing Mary’s handwriting so “decomposed my head” that he had to immediately close it and distract his thoughts.[26] He also pointed out to Anne Mozley that there is nothing “so painful as dismantling a home.”[27] In our contemporary world, situations similar to these have added complexities during a pandemic, especially if guidance prohibits households from mixing freely to support each other.

Newman drew great strength from celebrating Mass surrounded by the memorial cards adorning the wall of his private chapel. Supporting Mrs. Maxwell-Scott after the loss of her brother-in-law and uncle he writes:

“You have indeed accumulated sorrows. One’s consolation under such trials, which are our necessary lot here, is that we have additional friends in heaven to plead and interest themselves for us. This I am confident of—if it is not presumptuous to be confident—but I think, as life goes on, it will be brought home to you, as it is has been to me, that there are those who are busied about us, and in various daily matters taking our part.”[28]

Adapting insights from Joseph Butler’s work on religious analogy, John Keble’s poetic Christian Year, and the Alexandrian Fathers, Newman developed his sacramental principle to explain how we can continue to be influenced by the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus. In his Autobiographical Writings Newman reveals that he continued to sense Mary:

“Here everything reminds me of her. She was with us at Oxford, and I took delight in showing her the place—and every building, every tree, seems to speak of her. I cannot realise that I will never see her again.”[29]

He expands upon this reality in his sermon Gratitude in Christ:

“We naturally love places which remind us of friends; and sights and sounds (and scents) change in our estimate of them by our associating them with those we love—and thus pain loses its acuteness, and bereavement its heartache, and worldly anxiety no longer dries up the spirit, when we by faith regard them as memorials of Him who once was a man of sorrows for us and acquainted with grief.”[30]

The reassurance of Jesus’s continual presence, in grief, is balm for the bereaved. Newman perhaps had his ministry during the cholera epidemic of 1832 in mind as he concludes in his 1835 sermon, Tears of Christ at the Grave of Lazarus:

“Contemplating then the fulness of His purpose while now going about a single act of mercy, He said to Martha, ‘I am the resurrection and the Life: he that believeth in Me, though he were dead, yet shall he live, and whosoever liveth and believeth in Me, shall never die.’ Let us take to ourselves these comfortable thoughts, both in the contemplation of our own death, or upon the death of friends. Wherever faith in Christ is, there is Christ Himself. He said to Martha, ‘Believest thou this?’ Wherever there is a heart to answer, ‘Lord, I believe,’ there Christ is present. There our Lord vouchsafes to stand, though unseen—whether over the bed of death or over the grave; whether we ourselves are sinking or those who are dear to us. Blessed be His name! nothing [sic] can rob us of this consolation: we will be as certain, through His grace, that He is standing over us in love, as though we saw Him. We will not, after our experience of Lazarus’s history, doubt an instant that He is thoughtful about us.”[31]

Strengthened by the security of knowing that Jesus was with him in every setting, during the second, deadlier, national upsurge, Newman conducted the funeral of Edward Caswell’s wife, who, he informs Henry Wilberforce, “died by the most violent Cholera” within fourteen hours.[32] News of the Kent Oratory’s care of the stricken hop-pickers came to light. At the same time, back in Birmingham, Newman, together with Ambrose and Br. Aloysius, bravely responded to an emergency request to cover for a struggling priest. Bilston, nearby, was the centre of 3,568 cholera cases in 1832, where 742 people died. When Newman and his colleagues gave their pastoral support in 1849, there had been, in a two-month period, 1,365 deaths in the area and Wolverhampton, adjacent to it.[33] This prospect alarmed Newman’s parishioners who, he relayed to John Bowden, were crying as if he and his colleagues, “were going to be killed.”[34]

Although the immediate crisis receded after a few days, and he safely returned, he was profoundly affected by what he had witnessed, which can be seen in his letter to Jemima, written on 9 January 1850:

“I have seen very little of severe illness—but certainly the cholera is very shocking to see. We went over for a time to Bilston, where it raged so, that the priests were unequal to it. Multitudes crowded for reception into the church, and, alas, could not be received for want of instructors and confessors. They did not send for us till one priest was ill abed, and by that time the disease was abating—but the sight of the sick in the hospital was terrible—and brought before one most awful thoughts. The night calls, which were frequent, involving walks from nightfall to morning of four to (I think) seven miles were the most trying part of the toil, but I had none of that, though my dear companion had. Before we came, the priest had had in succession (the same priest) three or four journeys through the night—just getting into bed to be called out again. But I believe none died all through the country; whereas the fever the year before carried off, I think, at least thirty. A new year has commenced, and a new half century—great events are before us, though we may not live to see them.”[35]

Newman’s stark conclusion is very revealing. It indicates a real sense of trepidation in the wake of the illness. Amid the next national pandemic of 1854, he referred to the great work of the London-based Oratorians who offered themselves to serve the diocese, and were “in the thick of Cholera.”[36] Then, in 1857, at the University Church in Dublin—doubtless with knowledge of the Irish epidemics of the 1820s, 1830s, and especially 1848 in his consciousness—he reflected on the mission of St. Paul.

“He loved his brethren, not only ‘for Jesus’ sake,’ to use his expression, but for their own sake also. He lived in them; he felt with them and for them; he was anxious about them; he gave them help, and in turn he looked for comfort from them. His mind was like some instrument of music, harp or viol, the strings of which vibrate, though untouched, by the notes which other instruments give forth, and he was ever, according to his own precept, ‘rejoicing with them that rejoice, and weeping with them that wept’; and thus he was the least magisterial of all teachers, and the gentlest and most amicable of all rulers.”[37]

Newman incarnated his commentary on St. Paul among the sick and dying cholera victims and their families in Oxford, Birmingham, and Bilston.

[1] LD, ii, 59.

[2] LD, ii, 64n1.

[3] E. Ashworth Underwood, “The History of Cholera in Great Britain,” in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. xli (1947), 169–70.

[4] LD, iii, 7.

[5] Memorandum About the Cholera, (14 October 1874), LD, iii, 75.

[6] LD, iii, 68.

[7] LD, iii, 77.

[8] LD, iii, 91.

[9] LD, iii, 97.

[10] “Memorials of the Malignant Cholera in Oxford” (1835), 13, in LD, ix, 76n2.

[11] LD, xxvii, 13.

[12] LD, xix, 410.

[13] LD, xix, 311.

[14] LD, xix, 277.

[15] Newman, PS, vii (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1987), 1415.

[16] LD, iii, 55.

[17] LD, iii, 108.

[18] LD, ix, 76.

[19] LD, iii, 7.

[20] John Henry Newman Sermons 1824–1843, vol. ii, ed. Vincent Ferrer Blehl (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), sermon 22, 178.

[21] LD, xxiv, 150.

[22] LD, xxiv, 61.

[23] Newman, PS, v, 1143.

[24] Louis Bouyer, Newman His Life and Spirituality, trans. J. Lewis May (London: Burns & Oates, 1958), 109.

[25] LD, xxvi, 314.

[26] LD, ii, 91.

[27] LD, xxix, 227.

[28] LD, xxx, 67.

[29] Newman, AW, ed. Henry Tristram (New York: Sheed and Ward 1957), 213.

[30] John Henry Newman Sermons 1824–1843, ii, sermon 23, 183.

[31] Newman, PS, iii, 566-567.

[32] LD, xiii, 260.

[33] Underwood, The History of Cholera in Great Britain, 166–67.

[34] LD, xiii, 261.

[35] LD, xiii, 377–78.

[36] LD, xvi, 248.

[37] Newman, OS, sermon 8, 114.

Peter Conley

Assistant Priest at St. Joseph the Worker Church, Coventry, England

Fr. Peter Conley is the Assistant Priest at St. Joseph the Worker Church and Assistant Catholic Chaplain at Warwick University in Coventry, England. He has written articles on Newman’s bereavement letters for the <em>Newman Studies Journal</em>. His other research interests include: Newman’s colloquial expressions and the cultural references in his letters and diaries that especially reflect his humanity.

QUICK LINKS