Grit: A Lesson for Today's Catholics

On 12 September 1830 Newman preached a sermon in the University Church entitled “Jeremiah, A Lesson for the Disappointed.” It has not, so far as I am aware, ever attracted a great deal of attention. Though it was later published in Parochial and Plain Sermons—“the most important publication not only of Newman’s Protestant days, but of his life,” as Owen Chadwick once averred—it had to wait til volume eight for inclusion: hardly typical of “The Very Best Of …” territory.

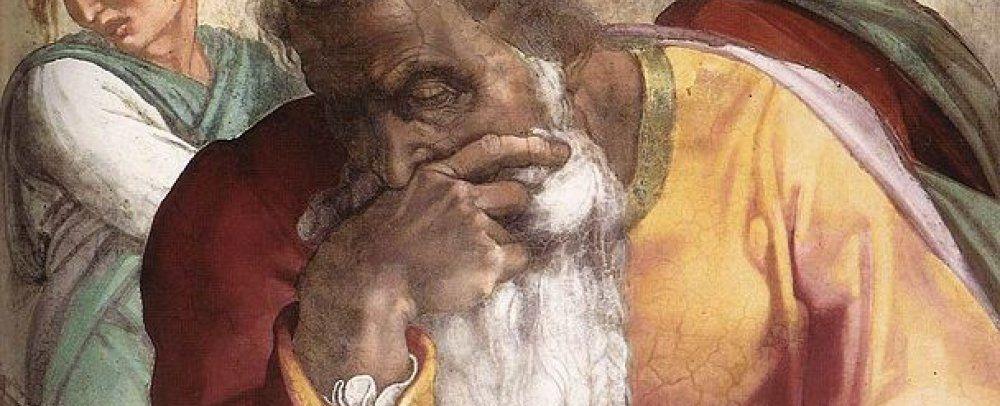

That is fitting in a way, however. For the whole topic of “Jeremiah, A Lesson for the Disappointed” is the fact of being overlooked, of deserving recognition but not getting it, of striving and failing—or rather, of seeming to fail.

Indeed, for Newman, “Jeremiah’s ministry may be summed up in three words, good hope, labour, disappointment.”1 No prophet, he argues, could reasonably have felt surer of success when starting out: “No prophet commenced his labours with greater encouragement than Jeremiah.” While only a child, Jeremiah was personally informed by “the word of the Lord” that:

Before I formed you in the womb I knew you,

and before you were born I consecrated you;

I appointed you a prophet to the nations. (Jer. 1:4–5)

Jeremiah certainly upheld his end of the bargain, devoting his entire life to his mission from God. This was, moreover, in the reign of King Josiah, and “there had not been a son of David so zealous as Josiah since David himself.” Accordingly, as Newman writes, “There seemed, then, every reason for Jeremiah at first to suppose that bright fortunes were in store for the Church … it seemed reasonable to anticipate further and permanent improvement.” And yet, to cut a very long story short, that is not quite how things worked out.

It is precisely this, according to Newman, that makes Jeremiah so important a model for Christians. When doing the Lord’s work, it is natural—though naïve—to expect that one will be successful, and abundantly so. And yet, often laboring in the vineyard turns out to be a hardscrabble kind of existence, materially and emotionally. A great deal of effort, but with little substantial to show for it.

Such work is not, however, futile. Rather, God plays a long game. A given person’s essential contribution, as Newman famously put it elsewhere, to God’s ultimate success may not become clear in their lifetime. Jeremiah’s certainly did not: he died, rejected and unheeded, in obscurity. And yet,

Look through the Bible, and you will find God’s servants, even though they began with success, end with disappointment; not that God’s purposes or His instruments fail, but that the time for reaping what we have sown is hereafter, not here; that here there is no great visible fruit in any one man’s lifetime.2

There is a great profundity in Newman’s words—and one that is, I have long been convinced, deeply applicable to our situation today. Doing the Lord’s work, building up the Kingdom, “answering the call” is a tough gig in contemporary America (as it is in many places elsewhere). With the long shadow of the abuse crisis, priest shortages, falling Mass attendances, parish closures, the rise of the nones, the after-effects of a global pandemic, the church’s pastoral work is all uphill.

In times like these, it is tempting to hope for a quick fix, a silver bullet, a bolt from the blue, that will result in some stunning reversal of fortunes. All things are possible. But, a more realistic, and likely much more successful, strategy will instead be to cultivate the attitude of Jeremiah. Newman calls it “resignation,” though his intended sense differs somewhat from how that term is understood today. I prefer to think of it as “grit.”

Give not over your attempts to serve God, though you see nothing come of them. Watch and pray, and obey your conscience, though you cannot perceive your own progress in holiness. Go on, and you cannot but go forward; believe it, though you do not see it. Do the duties of your calling, though they are distasteful to you. Educate your children carefully in the good way, though you cannot tell how far God’s grace has touched their hearts. Let your light shine before men, and praise God by a consistent life, even though others do not seem to glorify their Father on account of it, or to be benefited by your example.3

As a final aside, the more I (re)read Newman, the more I notice this spirituality of grit—what I sometimes like to think of as “the Little Way of the New Evangelization”—cropping up all over, and in much more well-known places in Newman’s writings. It is right there in his 1833 The Pillar of the Cloud (i.e., “Lead, Kindly Light”), as he keeps on keeping on through “th’encircling gloom,” one determined step at a time, “O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent.”

The spirituality of grit is there in his much-loved 1848 meditation “Some Definite Service,” where he points out that the indispensable role that God has assigned for him and him alone—“somehow I am necessary for His purposes… I have a part in this great work; I am a link in a chain”—may well not be obvious at the time: “I have my mission—I never may know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next.”

Lastly, grit is even there when Newman is at his most pastorally optimistic, basking in the sunny outlook of 1852’s “Second Spring”:

Have we any right to take it strange, if, in this English land, the spring-time of the Church should turn out to be an English spring; an uncertain, anxious time of hope and fear, of joy and suffering,—of bright promise and budding hopes, yet withal of keen blasts, and cold showers, and sudden storms?

If even at the best of times, God’s workers would do well to cultivate grit and perseverance, how much more do they need it today?

1 Newman, PS viii, 1868.

2 Newman, PS viii, 1868.

3 Newman, PS viii, 1868.

Stephen Bullivant

Stephen Bullivant holds professorial positions at St Mary’s University, London, and the University of Notre Dame, Australia. His most recent books are Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America (OUP, 2022) and Vatican II: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2023; co-authored with Shaun Blanchard).

QUICK LINKS