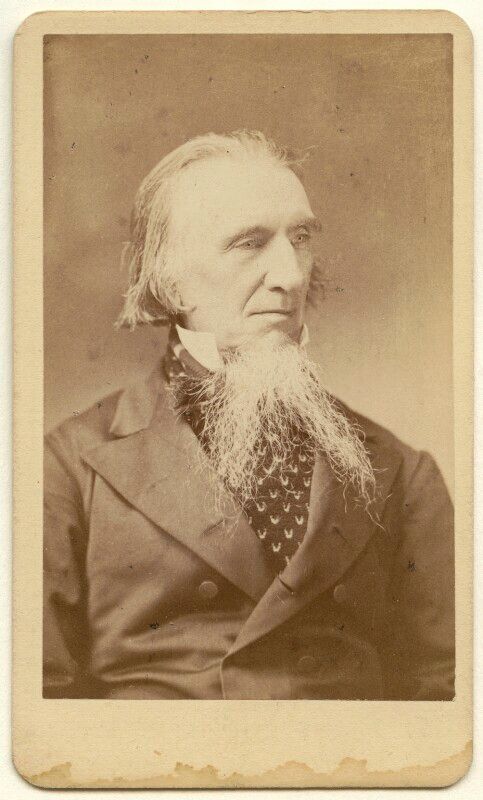

Charles Newman: The "Black Sheep" of the Newman Family

“The LORD is with me to the end. LORD, your mercy endures forever. Never forsake the work of your hands! – Psalm 138:8

The above verse is one of importance to John Henry Newman. He chose Psalm 138 as the epithet for his younger brother, Charles’s, headstone.[1] Newman’s biographer, Sheridan Gilley, refers to Charles as “the black sheep of the family.”

John Henry Newman was the eldest in his family, with his brothers Francis and Charles close behind him in age. John Henry had somewhat of a tumultuous relationship with both of his brothers. They often clashed in their philosophical, religious, and political thought, especially when John Henry decided to convert to Catholicism in 1845. Their beliefs mattered a lot to all three of them, though we do not have the clearest idea of what Charles’s beliefs were. While Francis and John Henry kept well-documented correspondence throughout their lives, the same cannot be said about John Henry and Charles. Upon Charles’s death, John Henry chose a verse that embodied his feelings about his somewhat estranged brother, which demonstrates that he still desired salvation for Charles, despite the worries Charles had caused his brother. Charles’s struggles help to reveal the role family played in John Henry’s life, as well as give us a better glimpse into the illusive brother many Newman scholars have encountered in name only.

Who Was Charles Newman?

Charles Newman’s story began much like John Henry’s. The brothers grew up in the same household with the same family. Born to John Newman (1767–1824) and Jemima Fourdrinier Newman (1772–1836) in 1803, Charles was the second youngest of six children. Though it is unclear from historical sources when the family realized that Charles exhibited behavioral difficulties, they were certain by the time Charles reached young adulthood that he suffered from “madness”—a nineteenth-century term used for a broad range of what we would think of today as mental illness. As early as 1821 their father noted that he was concerned about the “strained relationship” between Charles and the rest of his siblings, and his parents even had him checked for insanity twice, though a diagnosis for what we would think of today as mental illness was never recorded.[2] John Henry, though he had a strained relationship with Charles, tried to help him multiple times by finding him employment at the Bank of England and as an usher at a school. Due to his personal struggles, Charles spent much of his life alone, with most of his outside contact coming from his caregiver, Eliza Griffiths, in Tenby. For these reasons, Charles is nearly absent from the historical record. The little information we do know about him—his beliefs and his importance to the Newman siblings—comes from the correspondence between his siblings and their wives about his care, especially in their elder years.

Francis and John Henry Correspondence

Francis and John Henry maintained correspondence in which they discussed several mundane happenings in their lives, as well as more substantive theological and philosophical ideas. Philosophically, Francis and John Henry could not have been more different. Much like John Henry, Francis was well-learned, though he disagreed with his older brother on many fronts. For example, Francis once said when describing his own beliefs that he was “anti-everything.”[3] Francis believed in radical ideas about the economy. Francis’s “Lectures on Political Economy” would eventually even become a reference point for Karl Marx, particularly in vol. 3 of his Das Kapital. By 1843, John Henry was estranged from most of his siblings, except for his sister Jemima, due to his Catholic theological leanings.[4]Much like the rest of his family, Francis also strongly resented his older brother’s conversion to the Catholic Church in 1845. Despite these differences, the brothers maintained their correspondence concerning Charles’s care.

Charles’s Beliefs

As early as 1825, Charles had decided that he was no longer a believer in Christianity, opting instead for the anti-religious Socialist philosophy of Robert Owen, commonly known at the time as Owenism.[5] Charles’s philosophical conversion can be found in a string of letters he exchanged with John Henry. Charles, for example, wrote in a letter to his brother, “but I (after a great deal of preparatory thought, I acknowledge) have come to a judgement which no doubt will surprise you for it is entirely against Christianity.” He continues, “I think Mr. Owen for practical motives to action (for, since God has not pleased to discover himself to men, I admit not peculiar duty to him; except what consists in duty to our neighbor and ourselves) beats St. Paul hollow.”[6] Here, Charles admits that he has turned against the Christianity that has been so important to his brother. These letters between John and Charles are also an example of the intellectual character of the letters between the brothers.

The letters between Charles and John Henry are some of the few surviving documents that explain Charles’s beliefs in his own words because many of Charles’s papers were destroyed after John Henry purchased them back from Thomas Unwin of London.[7] Charles continues in his February 1825 letter to John Henry calling the principles of Owenism “approximately to truth,” while any other belief system is “acting and thinking on false principles.” Owenism had allowed Charles to see the world around him differently than he had before while a believer in Christianity. He says, “It is not Christianity that makes men good; it is men that ennoble Christianity. I do not deny the beauty of Christ’s precepts; but to make a system of them I consider very injurious: in fact it is religion immediately or obliquely that brings evil most abundantly into the world.” Charles believed the creation of systems around a specific religion to be a source of evil in the world. He acknowledged that his brother has a very different opinion than him, and in his response, John Henry argued with Charles about the heated nature of his newly-found ideals. Even though they found themselves in two very separate ideological spaces, the brothers continued to have intellectual conversations in their letters, which shows that they cared for each other’s minds.

Caring for Charles

John Henry and Francis were left to care for Charles after the death of their parents. The small inheritance left to Charles was quickly spent, and it became clear that someone had to provide for him. Sheridan Gilley argues that Charles’s choice to live off the wealth of his brothers was a product of his own choices. Despite their differences, the brothers still felt responsibility for Charles.

The many letters between Francis and John Henry demonstrate how Charles’s care kept them in contact. For example, a letter in November 1861 from Francis to John Henry, reads,

As I understand it to be really out of your superfluities, not out of your reasonable comforts, that you send me £20 for Charles, I gladly and thankfully accept it. But when you speak of him as a heavy burden to me, I think it well to assure you that we have always lived below our income, and of late so much … that Charles has never felt as in any material sense a burden.[8]

Often their correspondence consisted of a discussion of the financial care for Charles, followed by a brief statement about how he is doing. Much of how he was doing was relayed from Thomas Mozley, Jemima’s husband, to Francis who would then write to John Henry about the report. Occasionally, they would discuss other subjects, like in this letter from November 1861 where Francis writes about his thoughts on the American Civil War, though most of their letters were about Charles’s care.

Charles’s Death

Much of the correspondence about Charles deals with the financial nature of his continued care, particularly as they all aged. By the late 1870s and 1880s, John Henry and Francis found themselves corresponding about Charles’s financial care more often because of their old age and Charles’s failing health. In a letter from February 1884, Francis wrote, “The £500 which you gave me brings me for my life (if I remember) £92 a year, so that if I outlive CRN he is provided for entirely by your money without anything from me; for I pay Amy only £72 a year, the sum fixed by herself as that which she judged sufficient.” One month later, Francis reminded John Henry that he would have to be the one to pressure the rector to allow for burial in the Anglican church yard in Tenby because of his status in the Anglican church.[9] Francis wrote, “I should not desire to give CRN any more expensive burial than I have given to two valued servants … It is in your heart to press the Rector to allow burial in the Church Yard, —perhaps you will be willing to leave every detail to his entire discretion.”[10] Despite his own feelings about the funeral and burial of their brother, Francis understood that John Henry may value the burial of their brother more. In the same letter, Francis complained about the cost of Charles’s recent stay at a hotel due to his severe illness. Despite the financial nature of these conversations, the brothers remained in contact with one another even late in life.

Conclusion

On the one hand, Charles was John Henry’s brother who, despite their differences, he cared for. On the other hand, Charles had chosen to practice atheism against his brother’s wishes. John Henry struggled throughout his life with his own negative opinions of his brother. Gilley points out that the “aimless, profitless, forlorn life” lived by Charles demonstrated the pointlessness of existence without religion for John Henry.[11] We are left to believe that even despite his mental illness—deemed “madness” in nineteenth-century parlance—John Henry believed that Charles had actively chosen to live the way he did, which was likely due to the many chances for success in the public sphere that John Henry had presented to his brother. The way Charles chose to live his life reinforced John Henry’s own beliefs about the importance of leading a Christian life, which may be why the remaining correspondences between the two demonstrate an intellectual conversation about beliefs, rather than a conversation about the daily happenings in their life. This conflicted view of Charles may also be why John Henry acquired Charles’s letters for £15 after he had died. John Henry worried about the content of those letters and how, if publicized, it could possibly affect his brother’s reputation and his own.[12]

Though we do not have many of Charles’s personal writings, we can still gain a clear picture of who he was through the eyes of his brothers and other family members. In this case, we should recognize that the opinions expressed of Charles by his siblings are biased. For example, we can never know if his views of Owen’s philosophy were what drove him to depend financially on his brothers or if his personal struggles prevented him from doing anything more than that. Regardless of the unspoken biases, Charles played an important role in the lives of his two brothers. As much as they struggled to deal with his behavior, beliefs, and lifestyle, Francis and John Henry still found themselves responsible for his care. Even though they never saw eye-to-eye, John Henry and Francis found themselves continually brought together because of their brother’s needs, financial and otherwise. In some ways, Charles helped to keep the siblings together even despite the philosophical and religious differences that drove them apart.

[1] Sheridan Gilley, Newman and His Age (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1990), 410.

[2] Sheridan Gilley, Newman and His Age, London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1990, 56.

[3] Isabel Giberne Sieveking, "Memoir and Letters of Francis W. Newman", London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1909, 26.

[4] Gilley, Newman and His Age, 154.

[5] Gilley, Newman and His Age, 56.

[6] Charles Robert Newman to John Henry Newman (23 February 1825), NINS Digital Collections, B121-A016-D001.

[7] Thomas Unwin to John Henry Newma, (9 August 1884), NINS Digital Collections, B041-F001-D049.

[8] Francis William Newman to John Henry Newman (9 November 1861), NINS Digital Collections, B064-A004-D033.

[9] See Martin J. Svaglic, “Charles Newman and His Brothers,” PMLA 71, no. 3 (June 1956): 370–85.

[10] Francis William Newman to John Henry Newman (22 March 1884), NINS Digital Collections, B065-A001-D044.

[11] Gilley, Newman and His Age, 57.

[12] Gilley, Newman and His Age, 410.

Makenna Graves

Makenna Graves is a recent graduate of Duquense University’s Master of Arts in Public History Program. She was an intern at NINS during her spring 2023 semester. She is interested in 18th/19th century history and museum education. Makenna will soon be starting a position at the National Museum of the United States Army and looks forward to her future as a public history practitioner.

QUICK LINKS