Bicentenary of Newman’s ordination to the diaconate in the Established Church

Two hundred years ago, on Sunday 13 June 1824, John Henry Newman was ordained a deacon of the Church of England in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. In preparation for this momentous day, he had been fasting for three months. Two days before taking holy orders, he wrote in his private journal (which acted as a prayer diary), “As the time approaches for my ordination, thank God, I feel more and more happy. Make me Thy instrument … make use of me, when Thou wilt, and dash me to pieces when Thou wilt. Let me […] be Thine.” On the eve of his ordination, however, he records that he was assailed with doubts about “whether the office is so blessed, the Christian religion so true” and, feeling “how hard my heart is, how dead my faith,” about taking so “irreparable a step.”1

The entry for 13 June in his diary (which, unlike his journal, he used simply for recording facts) is typically terse – “ordained Deacon in Ch Ch”2 – but his private journal records his innermost feelings:

It is over. I am thine, O Lord; I seem quite dizzy, and cannot altogether believe and understand it. At first, after the hands were laid on me, my heart shuddered within me; the words ‘for ever’ are so terrible. … At times indeed my heart burnt within me, particularly during the singing of the Veni Creator. Yet, Lord, I ask not for comfort in comparison to sanctification.3

The following day he wrote, “‘For ever,’ words never to be recalled. I have the responsibility of souls on me to the day of my death. … What a blessed day was yesterday. I was not sensible of it at the time – it will never come again.” 4 A year later, on 29 May 1825, Newman was ordained an Anglican priest.

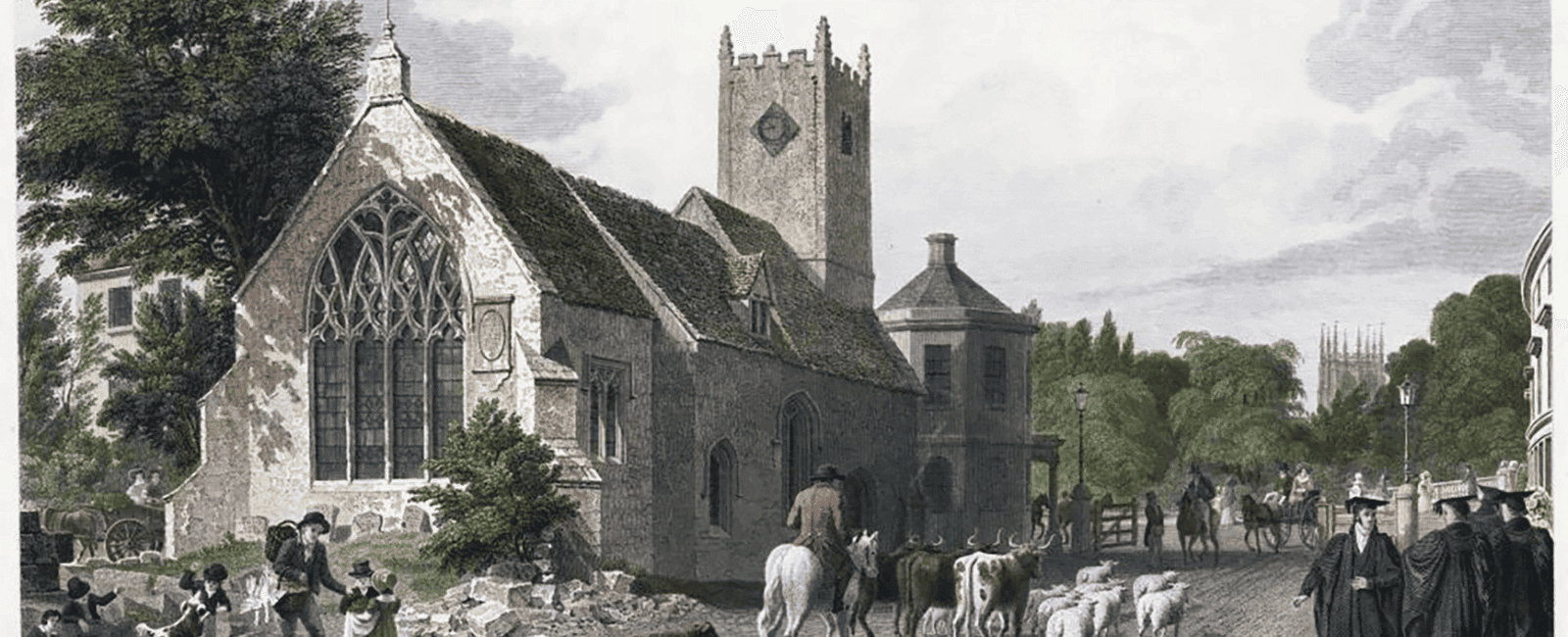

After finishing his undergraduate studies at Trinity College in 1820 – he read both Classics and Mathematics – Newman remained in Oxford hoping to gain a fellowship at one of the colleges, though his father had enrolled him at Lincoln’s Inn with a view to his son entering the law. In April 1822 he was elected a fellow of Oriel College, then the leading college of the university. That year Newman decided to take holy orders. At the time, more than half of Oxford graduates proceeded to holy orders, and a still greater proportion of fellows did so, resigning their fellowships in order to marry (as, at the time, fellows had to be unmarried) or else to take up a “living” (i.e. a curacy within an Anglican parish). Though this did not necessarily translate into “a deeper engagement with ordinary people’s pastoral and spiritual affairs,”5 in Newman’s case it did. A month before he was ordained, on 16 May, he accepted the curacy of St. Clement’s, a rapidly growing working-class parish adjoining the university.

There were around 1500 souls in the parish of St. Clement’s, but the rector, John Gutch, was in his late seventies and infirm. The plan was to demolish the church and rebuild a larger one nearby, but a curate was needed as “a kind of guarantee to the subscribers that every exertion will be made, when the Church is built, to recover the parish from meeting houses [i.e. non-conformist churches], and on the other hand alehouses, into which they have been driven for want of convenient Sunday worship.” Newman anticipated that the curacy was “likely to give much trouble” and was particularly worried about the weakness of his voice – not a trivial consideration, given that he would be required to read Scripture and give lengthy sermons at Sunday services. But, on the encouragement of five fellows at Oriel,6 who knew him well, and of Rev. Walter Mayers, he decided to accept it. As his journal reveals, he was fully aware of what he was taking on: “When I think of the arduousness, I quite shudder. O that I could draw back, but I am Christ’s soldier. Every text on the ministerial duty and my ordination vows, within this last day or two, come home to me with tenfold force.”7

The most influential figure on Newman at the time was Walter Mayers. In the aftermath of the collapse of his father’s bank in March 1816, Newman had stayed on at Ealing School during the summer vacation, where he was thrown into the company of Mayers, the senior Classics master and a devout evangelical. During this time, he fell seriously ill. Deeply influenced by the sermons, conversations and suggested reading of Mayers, that autumn he experienced the religious conversion that he regarded as the most momentous event of his life and from which he emerged as a believing Christian.8 Going up to Trinity College at the tender age of sixteen was a chastening experience for the earnest young man of Calvinist leanings, who found himself among sixty undergraduates, all older than himself, not over-studious, and given to enjoying life. As Newman would later say, it was the support of Mayers which helped him through “the dangerous season of my Undergraduate residence,”9 by warning him not to associate with those who were dissipated and instead to seek out select friends, and by urging him to face up to the dangers of residence at Oxford and endure the “ridicule of the world.”10

When Mayers dined at Oriel as Newman’s guest in February 1823, Newman consulted him about whether he should be ordained as soon as possible. Mayers encouraged him to do so. Though other friends advised him to wait, Newman followed the advice of Mayers. Newman’s letters, diary, and journal give few clues about his preparation for ordination, but judging by the number of visits he paid to Mayers, it would appear that Mayers was his primary mentor at the time. In September 1823 Mayers accepted the curacy of Holy Trinity, Over Worton, nearly twenty miles north of Oxford, and that month Newman stayed with him and his wife for three weeks. In 1824, prior to his ordination, Newman spent a further nine days with him, walking or riding to Over Worton on four occasions.11

The official preparation for ordination stipulated by the university was that ordinands should attend a series of lectures given by the Regius Professor of Divinity. The scholarly, “high-and-dry” Charles Lloyd had just been appointed to the post, and he decided to experiment by giving some private lectures conducted in an informal, interactive fashion. They focused on his own interests, which included exegetical criticism and historical research, rather than dogmatic theology. The private lectures that Newman attended began with three other fellows from Oriel and four from Christ Church, but others joined later. Lloyd soon noted that Newman held evangelical views of doctrine, which were generally looked down on in Oxford at the time, and ribbed him in friendly fashion, pretending to “box his ears or kick his shins” as he passed Newman while he paced up and down his room.12

It is worth noting that by taking on the curacy of St. Clement’s, Newman managed to alleviate one of his pressing concerns. Three years earlier, in November 1821, his father had declared bankruptcy. As the eldest of six children, the responsibility for his mother and five siblings fell on John Henry, as did the mounting debts of his aunt Elizabeth. His journal entries at the time are littered with references to financial worries and show that he constantly turned to prayer in his need: “I am so straitened for money – and I prayed more earnestly than usual for relief. The post has brought […] £25”;13 “I owe much; many bills should have been paid long ago. […] O gracious Father, how could I for one instant mistrust Thee? On entering my room, I see a letter containing £25!”14 In the years before being elected a college tutor in 1826, Newman took on as much private tutoring as he could handle – up to six hours a day. He also accepted commissions for articles, such one on logic and another on Cicero for the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana. The curacy of St. Clement’s would bring in a salary of £45 p.a. plus around £10 for “surplice fees.”

But the relief of financial worries was not uppermost in Newman’s mind. Shortly after accepting the curacy, he told his father, “I am convinced it is necessary to get used to parochial duty early, and that a Fellow of a College, after ten years residence in Oxford, feels very awkward among the poor and ignorant.”15

On Sunday 4 July Newman took his first service at St. Clement’s, then “read” in church in the afternoon, performed his first baptism, and visited a sick parishioner. The following Sunday he officiated at his first wedding. In the intervening days he visited the sick, conducted more christenings, and attended his first meeting of the committee for the new church. Two of the parishioners he called on, by the name of Odcroft and Swell, were dying and in need of spiritual support. In these, as in other cases, Newman took detailed notes about his visits. These first-hand reflections on the reality of conversion, regeneration, faith and grace helped him to see that the standard Calvinist division of Christians between “real” and “nominal” was untenable. Years later, he remarked that “Calvinism was not a key to the phenomena of human nature, as they occur in the world.”16

Mr. Odcroft had an inflamed liver and during the five weeks Newman cared for him, he visited his house on twenty-five occasions. After his death on 9 August, on discovering that Odcroft had taken to the bottle, Newman admitted to himself, “I fear I did not go to the bottom, but want experience. Though I told him openly the grand doctrines of Christianity, I did not say [he] must be born again, but that he must have faith, abhorrence of sin, etc. […] I was too gentle. Lord, pardon me.”17

Newman’s notes on Mr. Swell, who had cancer of the throat, are more detailed as he visited him over a period of five months until his death on 16 November. Once a prosperous farmer, now – in Newman’s estimation – a “very bad character,” Swell initially refused to receive Newman and spent his time at the local pub, when well enough. After persisting, Newman managed to speak to him about the need to admit he was a sinner, to allow himself to be prayed for, and to receive communion, but Swell fought off these advances. Sometime later Swell wanted “to rely on Christ,” but “without change of heart.” At last, he changed and in tears begged Newman to pray for him and to visit him frequently. “After some days he was brought into great comfort and peace. He grew weaker and weaker and at length departed (as I trust) in the Lord. Amen.” His “agonies,” according to the doctor who attended him, “were indeed extraordinary. The whole of this time God seemed to be drawing him and he at last owned it and felt it. There was something sudden certainly in the transition from obstinacy to terror and from terror to faith: but it might appear more sudden than it really was.”18

Over a period of four months Newman visited Swell on twenty-four separate days, sometimes seeing him twice a day. Towards the end, besides taking him communion, Newman brought him wine or port to ease his sufferings. All these visits were on top of dealing with his father’s last illness and death in London on 29 September, then organizing his funeral and sorting out the family papers. There were around two dozen other sick and dying people that Newman cared for during his 21 months at St. Clement’s, and notes on many of them survive.19 Describing parochial duties to his friend Edward Pusey, Newman explained that the “most pleasant part of my duties is visiting the sick […] My visits quite hallow the day to me, as if every day was Sunday.”20

Towards the end of his first week in the parish, it transpired that the rector had no list of parishioners. It seems that, to make amends for his negligence, Gutch presented Newman with Speculum Gregis [Mirror of the Flock]; or, Parochial Minister’s Assistant, by a Country Curate (1820), with a dedication to Newman dated July 1824.

On Saturday 17 July, Newman embarked on a visitation of the parish, house by house. Within two months he had completed the task and compiled a list of the names, addresses, and trades of everyone in the parish. These visits taught him that “the readiest way of finding access to a man’s heart, is to go into his house.”21

The Speculum Gregis is a pocket-sized logbook with a short introduction. The bulk of the book was intended to be used by clergymen to record details of their parishioners. Each double page is divided into columns under ten headings: 1) House No., 2) Names of Inhabitants, 3) Occupation, 4) When Born, 5) General Health, 6) Attends Church and Sacraments, 7) Uses Family Devotion, has a Bible or Prayer Book, 8) Attends other Services, 9) Reads, Writes or goes to School, and 10) Observations. Newman owned two copies, both dated July 1824: the first edition of 1820 and an 1823 edition. Both have been filled in with the names and occupations of the parishioners Newman visited, but with few other details. (His reflections on his visits to the sick were kept separately in a private notebook.) The trades of the parishioners included poulterers, fruiterers, upholsterers, tailors, shoemakers, college servants, coachmen, schoolteachers, and a clerk of works.22

This was probably the first time that Newman had come into close contact with tradesmen and their families. Starting his visits with “the most respectable” parishioners, he told his mother, “I shall know my parishioners, and be known by them.”23 To his father, he explained that he had told them, “I count you all my flock, and shall be most happy to do you service out of Church, if I cannot within it.”24 This highly relational approach was to color all his pastoral, and therefore educational, work over the next six decades.

Having thrown himself into parish life, Newman found that his duties left him little time for his devotions and private study of scripture, and that he was neglecting his time for self-examination.25 It was probably in reaction to this neglect that he compiled a detailed list of prayer intentions for the academic year 1824–1825. Each day of the week had its own intentions. One of the four intentions for Tuesdays read:

Intercede for:

flock at St Clements, churchmen, dissenters, romanists [i.e. Roman Catholics], those without religion. Pious, worldly. Rector, churchwardens, and other offices. Sick, old, young, women labouring with child. Rich and poor, schools.

His prayer intentions for Saturday were entirely devoted to the parish:

Pray for: Usefulness

Mean and opportunity of serving the poor, obliging the more wealthy, edifying all. For success in preaching, visiting, calling, teaching, reading, catechising.

Pray for:

In the parish, vigilance, alertness, unweariedness, presence of mind, meekness of wisdom, simplicity, quietness, power of reply, love, humility, discerning of spirits

In visiting sick, lowliness, mercy, dependence on Christ, judgement, knowledge, firmness, candour.

In catechising, patience, gentleness, kindness, cheerfulness, clearness in teaching, wisdom.

Towards dissenters, humility, charity, mercy, forbearance, wisdom, a word in season.26

In order to launch an appeal for the parish church Newman approached friends and others at the university for subscriptions, as well as asking everyone in the parish itself. By December he had secured £551 from 32 individuals and another £420 from within the parish. A meeting took place at the town hall on 7 December 1824 to officially launch the appeal. Within a year the total raised was £4,333, which was sufficient for building works to start in 1826.

Early in 1825, once the appeal had been launched, he oversaw the building of a gallery in the church to accommodate a Sunday school for the children of the parish. Pusey provided the stove. Besides all this work, and his private tutoring and college duties – he was elected Junior Treasurer in October 1824 – Newman took his preaching seriously, so much so that students and fellows began to attend St. Clement’s to hear him. Such energy was uncommon at the time with Anglican clergymen, and explains an entry in Newman’s journal, “I find I am called a Methodist.”27

What does all this tell us? Surely, that Newman’s engagement with parish life gave him the insights into lived, real faith that allowed him to make his historic theological contributions in such works at Lectures on Justification (1838) and the Grammar of Assent (1870).

Newman preached his first sermon (the handwritten text of which is available on the NINS Digital Collections) on 23 June 1824, not at St. Clement’s but at Holy Trinity, Over Worton. That story will be taken up in a separate article.

1 Newman: AW, ed. H. Tristram (London: Sheed & Ward, 1956), 200.

2 LD i, 177.

3 AW, 200. The ellipsis indicates text which Newman wanted to omit when he copied out the parts of his journal that he did not wish to destroy.

4 AW, 201.

5 James Arthur and Guy Nicholls, John Henry Newman: Continuum Library of Education Thought, vol. xviii (London: Continuum, 2007), 19.

6 Edward Hawkins, Richard Jelf, John Ottley, Edward Pusey, and James Tyler.

7 (16 May), AW, 198–99.

8 Although Newman became what might loosely speaking be termed a Calvinistic evangelical, his was “quite unlike the standard form of Evangelical conversion, of conviction of sinfulness and the sensation of transforming release by divine deliverance from it.” Instead, he saw it as a personal call to holiness, rather than an assurance of salvation freeing him from the need to obey the moral law and adopted a more doctrinal form of Christianity. Sheridan Gilley, “Life and writings,” in The Cambridge Companion to John Henry Newman, ed. Ian Ker and Terrence Merrigan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 2.

9 Newman to Greaves (27 February 1828), LD ii, 58.

10 Mayers to Newman (16 June 1817), LD i, 36n.

11 His diary records visits to Over Worton on 25 February, 3–5 and 17–20 April, and 2 June.

12 See AW, 69–72 for a description of Lloyd and his private lectures.

13 (4 November 1823), AW, 194.

14 (9 February 1824), AW, 196.

15 Newman to his father (25 May 1824), LD i, 175.

16 AW, 9.

17 LD i, 177.

18 LD i, 178.

19 These “case studies” have received scholarly analysis by Robert Christie in The Logic of Conversion: The Harmony of Heart, Will, Mind and Imagination (New York: Angelico, 2022), 101–21. See also Geertjan Zuijdwegt, An Evangelical Adrift: The Making of John Henry Newman’s Theology (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2022), ch. 3, for an analysis of Newman’s changing theological convictions at the time.

20 Newman to Pusey (17 September 1824), LD i, 191.

21 Cited in Gerhard Skinner, Newman the Priest: A Father of Souls (Leominster: Gracewing, 2010), 9. Note that the reference Skinner gives (LD i, 179n) is incorrect.

22 The two copies of the Speculum Gregis can be found in Birmingham Oratory Archive, A 12.3.

23 Newman to his mother (28 July 1824), LD i, 180.

24 Newman to his father (9 August 1824), LD i, 184.

25 (21 February 1825), AW, 205.

26 Birmingham Oratory Archive, A 10.4. There are two versions of this list of petitions. The other can be found in Vincent Ferrer Blehl, Pilgrim Journey: John Henry Newman 1801–1845 (London: Burns and Oates, 2001), 419–23.

27 (21 February 1825), AW, 204.

Share

Paul Shrimpton

Paul Shrimpton teaches at Magdalen College School, Oxford. Over the last thirty years he has published articles, chapters and books on Newman and education. His Newman and the Laity will appear in 2025.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS