Bicentenary of Newman’s First Sermon

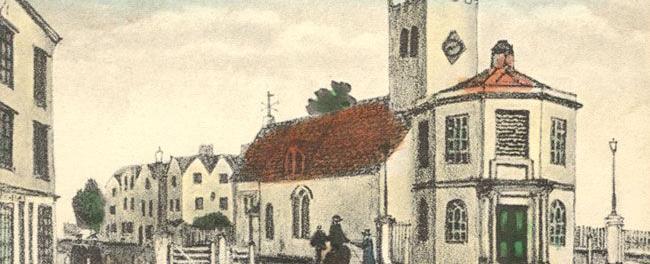

Two hundred years ago, on Wednesday 23 June 1824, John Henry Newman preached his first sermon. It was delivered in the evening at Holy Trinity Church, Over Worton, a village seventeen miles north of Oxford, in the parish of Rev. Walter Mayers, who had been Newman’s principal mentor since the religious conversion he underwent in 1816. Four days later, on Sunday 27 June, Newman took up duties as curate in the parish of St. Clement’s, Oxford and preached his second sermon at a morning service presided over by the elderly rector, John Gutch. The following Sunday, 4 July, Newman took the service himself and reused the sermon he had preached at Over Worton. During his nineteen months as curate at St. Clement’s, Newman prepared and preached 150 different sermons, a most unusual feat for a newly ordained clergyman.

Newman’s reputation as one of the greatest preachers in modern times is so widespread that it needs no comment. It was during his years as vicar of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford, 1828–1843, that he reached the height of his preaching fame. Besides deeply affecting his hearers, Newman’s influence from the pulpit reached countless others via the printed word. Six volumes of his Parochial Sermons appeared between 1834 and 1842, and Plain Sermons in 1843. Most readers are acquainted with them as the eight-volume series Parochial and Plain Sermons, the form in which they were republished in 1868. In 1843 Newman published his Oxford University Sermons – lectures in all but name – and a miscellaneous collection entitled Sermons on Subjects of the Day.

Learning the Art of Sermon Composition

From 1824 to 1843 Newman was an active clergyman of the Church of England engaged in a continuous ministry of preaching. Soon after arriving at St. Clement’s, he began preaching twice on a Sunday, once in the morning and once in the afternoon, a practice he continued for most of his years at St. Mary’s. In addition, there were the sermons that he delivered on saints’ days, at Littlemore, and when taking services for friends or others elsewhere. When Newman began composing his sermons in June 1824, he numbered them, a practice he continued up to his last sermon in the Church of England, No. 604, better known as “The Parting of Friends.” Many of the sermons were used on more than one occasion – though not for the same congregation – in some instances as many as seven or eight times. In reusing a sermon, Newman made revisions and alterations, which, in some instances, amounted to a virtual rewriting. During his nineteen years an Anglican clergyman, Newman entered the pulpit around 1,270 times.

Not long after taking up the curacy of St. Clement’s, Newman became aware that he was beginning to attract students and academics from the university. It might seem surprising, therefore, that he should remark that none of his sermons “preached at St. Clement’s, 1824–26” were “worth anything in themselves,” but for the fact that they “show how far I was an Evangelical when I went into Anglican Orders.” 1

The Newman scholar Gerard Tracey maintains that “It was not until October 1831 that he hit upon his own personal approach to sermon composition.”2 This means that over a period seven years, 1824–1831, Newman was hard at work honing his style. What may console those who have to prepare sermons is Newman’s comment on 15 August 1824: “Two sermons a week very exhausting. This is only the third week, and I am already running dry!”3

Newman’s pastoral sermons generally lasted forty-five minutes. The text was written out beforehand on some twenty sheets of paper, with the facing pages kept blank for alterations, in case the sermon was reused and for comments. He usually spent two to three days on each sermon. Once completed, he would read the sermon through, making alterations as he went along: adding or deleting a word, phrase or sentence, and on occasions rewriting whole sentences, paragraphs, or sections. Then, just before the service, he would touch it up one last time. During his nineteen months at St. Clement’s, Newman wrote approximately one quarter of his Anglican output. At no other period did he compose so many sermons for such an extended period of time. It is difficult to say what effect this had on his correspondence, as he destroyed most of his letters from this period, as well as parts of his private journal. Newman also compiled abstracts of his sermons, presumably as a way of analyzing them, a practice he abandoned after leaving St. Clement’s. To judge from the comments on them, he was particularly critical of his early sermons. Comments range from “scanty” and “very indifferent” to “not quite correctly analysed, the didactic and hortative parts being mixed together,” “deficient in division, matter, and practical application,” and “decidedly the worse I have done.”4

Newman undertook hard reading for many of his early sermons as he tried to sort out his theological ideas and gain inspiration from others. His notes on sermon 16 (no. 20), for example, indicate that he consulted ten different authors.5 (Note that sermon 16 [no. 20] means it was the sixteenth to be preached, but the twentieth to be written.) In sermon 21 (no. 28), Newman draws heavily on an outline of a sermon by George Simeon, the influential evangelical clergyman at Cambridge, and in sermon 58 (no. 85) on Simeon’s sermon “A good and evil Conscience.” The work consulted was Simeon’s Helps to Composition; or, Six Hundred Skeletons of Sermons, several being the substance of sermons preached before the University (5 vols, 1815). In sermon 67 (no. 103), Newman draws extensively on the long introduction to Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed (1736) by the leading evangelical Daniel Wilson. It was not long before Newman began having second thoughts on the evangelical view on baptismal regeneration, election, human corruption, predestination, justification, and “real” and “nominal” Christians.

As early as 24 August 1824 Newman records in his prayer journal his considerable unease:

Lately I have been thinking much on the subject of grace, regeneration, etc. and reading Sumner’s Apostolic Preaching […]. Sumner’s book threatens to drive me either into Calvinism, or baptismal regeneration, and I wish to steer clear of both, at least in preaching. I am always slow in deciding a question; last night I was so distressed and low about it, that […] the thought even struck me I must leave the Church. I have been praying about it […] and do not know what will be the end of it. I think I desire the truth, and would embrace it wherever I found it.6

On a house visit a few days later, Newman was told by a married couple that they hoped he would be “more Calvinistic.” “What shall I do?,” he wrote in his journal, “I really desire the truth.”7 His anxiety arose not so much from academic perplexity as from an awareness that “I have the responsibility of souls on me to the day of my death.”8 Five months later another journal entry offers a window into his mind and heart:

The necessity of composing sermons has obliged me to systematize and complete my ideas on many subjects – on several questions, however, (those connected with regeneration) though I have thought much, and (I hope) prayed much, yet I hardly dare say confidently that my change of opinion has brought me nearer to the truth. At least, however, I may say that I have taken too many doctrines almost on trust from Scott etc and on serious examination hardly find them confirmed by Scripture. I have come to no decision of the doctrines of election etc, but the predestination of individuals seems to me hardly a scriptural doctrine.9

Though his sermons soon saw the congregation at St. Clement’s grow, some parishioners expressed their concern that he was too stern and somber. Word reached him via his friend Edward Pusey that his parishioners liked him greatly, but that “I damned them too much.” In his journal Newman comments that “I was at first perplexed,” then “afterwards I thought it must mean I dwelt much on the corruption of the heart – and that explained it. Give grace!”10 Over his nineteen months at St. Clement’s, Newman’s theology was developing – and it continued to do so until he entered into full communion with the Catholic Church in 1845. Too often, however, academic theologians treat Newman as if he were one of their own and assume that the development of his theology was driven solely by his reading and research. They overlook the fact that he was constantly dealing with souls and that his abiding concern was whether his theological thinking was the key to understanding the human condition. Newman was not so much an academic theologian as someone interested in theology insofar as it enabled him to deepen and live out its implications, and to help others to do so, too. Thus, his thinking and practice continually infused and informed each other. Rather than engage with theological systems, Newman turned to the individual in his or her particular setting.

Getting to know his flock

On Saturday 17 July 1824, Newman embarked on a visitation of the parish, house by house. Within a month he had called on around four hundred houses and come into contact with some 1,400 individuals. Their names and occupations are recorded in his two copies of Speculum Gregis [Mirror of the Flock]; or, Parochial Minister’s Assistant, by a Country Curate, a recently published logbook to help clergymen record details of their flock. The trades in the parish include: apprentice, artist, attorney, auctioneer, baker, book-binder, brewer, builder, butcher, butler, carpenter, chandler, charwoman, coachman, cobbler, cook, cooper, engraver, fruiterer, gaiter-maker, glass-stainer, governess, greengrocer, hairdresser, labourer, militia man, ostler, poulterer, publican, saddler, servant, shoemaker, smith, tailor, tinman, and umbrella-maker.11 It was to ordinary folk such as these to whom Newman ministered. Although his father did not approve of these visits, on the grounds that an Englishman’s home was his castle, John Henry disagreed. “In all places,” he told his father, “I have been received with civility […] in most with cheerfulness and a kind of glad surprise, and in many with quite a cordiality and warmth of feeling.” Only recently had he written in his journal, “I am more convinced than ever of the necessity of frequently visiting the poorer classes – they seem so gratified at it, and praise it.”12

Among those visited was the local dissenting minister, Mr. Hinton, as well as the resident Catholic parish priest, Robert Newsham (in whose church he would attend mass on Sunday 12 October 1845, three days after becoming a Catholic). He told his father:

I have not tried to bring over my regular dissenter […] A good dissenter is of course incomparably better than a bad Churchman, but a good Churchman I think better than a good dissenter. There is too much irreligion in the place for me to be so mad as to drive away so active an ally as Mr Hinton seems to be.13

Two days after completing his parish visitation, he started a second round, this time seeking subscriptions for the building of an enlarged St. Clement’s on a nearby site. In addition to home visits and fund-raising activities, life as a curate was a never-ending round of baptisms, “churchings,”14 weddings, visits to the sick and dying, and funerals. His first baptism and churching took place on his second Sunday at St. Clement’s, and a week later he officiated at his first wedding. His first burial was that of a child whom he had baptized a fortnight earlier. In October 1824 Newman took on the role of Junior Treasurer at Oriel, then in March 1825 he agreed to become the vice-principal of St. Alban Hall, a small independent academic hall of the university. St. Alban’s Newman gave most of the lectures, set the weekly compositions, and dined with them three times a week. Additional income was generated when he undertook to write more articles for the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana, one on “Miracles” and another on “Apollonius of Tyana,” along with a book review for the Quarterly Theological Review. He had attended the private lectures of Charles Lloyd, the Regius Professor of Divinity (and later Bishop of Oxford), preparatory to his ordination to the diaconate in June 1824 – and continued doing so up to his ordination as an Anglican priest the following year. This entailed a good deal of serious reading. On top of this, he was engaged for seven months in a lengthy correspondence with his brother Charles, who had abandoned the Christian faith.

By the middle of January 1826, pressure of work had taken a toll on his health, and he suffered chronic indigestion.15 Two years earlier he had been concerned about whether his voice was strong enough for preaching. This concern was rekindled shortly after preaching his first sermons, on being told that he had not spoken loudly enough from the pulpit.16 The following Sunday, after preaching three sermons, he noted in his diary, “think I have found out the secret of my great weakness of voice – drank several glasses of wine today […] and my voice was pretty strong.”17 A week later he says that he has “adopted the measure” on a regular basis! No personal reminiscences have come down to us from those who heard his early sermons, but those who heard him preach a decade later at St. Mary’s describe how he addressed his congregation in a “low, soft, but strangely thrilling voice,” which “left unforgettable memories with many of his listeners.”18 He also avoided the then-usual oratorical devices of the pulpit.

“Waiting on the Lord”: Newman’s first Sermon

We have, therefore, to use our imagination when we listen to “Waiting for God,” the first sermon Newman preached, on Sunday 23 June 1824. His opening words were from Psalm 27:14, ‘Wait on the Lord: be of good courage, and He shall strengthen thine heart: wait, I say, on the Lord.’

It is worth reading the three short paragraphs with which Newman began his preaching career, even though he did not consider the sermon worth publishing. From the outset he speaks to his congregation in simple, plain prose, yet he soon begins to suggest how inconsistent most Christians are.

The necessity of perseverance is felt and acknowledged in every pursuit and business except in religion. Difficulty and delay, disappointment, failure, opposition are expected as matters of course by the merchant or trader, the candidate for literature distinction, or the aspirant to popular applause. We are accustomed to say “slow and sure” to praise patient industry which saves and toils in the hope of becoming rich, and we admire and honor the strength of mind which enables a man contentedly to plod on from year to year in laborious researches, for the sake of at length acquainting the world more fully with the nature of languages or the customs of people, which have now for thousands of years ceased to exist.

Such is the wisdom of men in worldly matters – but in religion we find them altogether reverse this rational plan of proceeding. A knowledge of religion is to come of itself – or the acquisition of it is to be thrust off to the end of life, and then made all of a sudden – or the practice of it is made to consist merely in certain outward ceremonies – or in a mere activity and usefulness of life – or in mere innocency of temper and amiableness of manners.

Surely they are more consistent and act more rationally who deny the importance of religion altogether, than those who confess its high claims upon our attention and yet take such idle measures, make such feeble exertions in the most awful of all enterprises, for the most glorious of all rewards. Our text however gives us a different lesson – “Wait on etc.”19

There is something distinctly Newmanian about these opening lines, in the way a seemingly unpromising comparison is brought to bear and the listener invited, if not stirred, to change his or her life. Shortly afterwards, he throws out a stark summons to abandon mediocrity, when he says, “The greater part indeed of professed Christians, so far from waiting on the Lord, scarcely ever think about Him – and their religious profession (such as it is) is adapted to quiet their consciences or inflate them with self-righteousness, rather than to satisfy the desires of the renewed mind.”20 Like other Newman sermons, there are no vague platitudes or pious aspirations. Instead, the hearer is exposed to a shrewd practical psychology and a demanding spiritual realism.

Newman’s first preached sermon contains no fewer than 53 scriptural quotations, some of which are closely grouped for dramatic effect. His ability to deploy Scripture so readily testifies to his close reading and familiarity with the Bible, as well as to his prodigious memory. In the year before his ordination to the diaconate we read in his private journal comments such as: “Last week or two I have been learning Scripture by heart, and have just finished the Epistle to the Ephesians”; “I have learned eight chapters of Isaiah by heart […] May they be imprinted on my heart as well as on my memory.”21 Presumably, he foresaw that committing Scripture to memory like this would help him in his preaching.

Very few are aware that Newman also wrote out sermon abstracts, for the simple reason that he only drew them up for the nineteen months he was at St. Clement’s – and that they became accessible with the publication of John Henry Newman: Sermons 1824–43 (1991–2012, 5 vols). The abstracts show that behind the sinuous prose and absorbing line of thought, there was a clear structure, as shown by the abstract for sermon 1 no. 2):

Introduction – we think perseverance necessary in all things but religion.

Definition of waiting

We wait on God.

1. for light, holiness and comfort here.

2. for perfection and glory hereafter.

Our subject concerns

I. religious inquirers – i.e. those who wait for light waiting necessary

1st from analogy of natural discoveries.

2nd from importance of the subject

3rd from the Bible cutting both ways.

– tests of a sincere inquirer

1st he studies his Bible continually

2nd he prays earnestly

3rd he acts up to his light.

II. those who are grounded in the faith, i.e. who wait for holiness, comfort, etc etc.

1st for deliverance from worldly trouble – soberly

2nd for spiritual comfort – more earnestly

3rd for holiness – most earnestly

4th for the extension of Christ’s Kingdom

5th the last judgment

Conclusion – the opposite feelings of good and bad at that judgment.

Though “Waiting for God” was the first sermon Newman preached, it was not the first that he wrote. “The work of man,” sermon 2 (no. 1), was the first to be composed, though the second to be delivered, based on Psalm 104:23, “Man goeth forth unto his work and to his labour until the evening.”

There is no need to comment on these and other early sermons of Newman’s, as there exists a rich literature on his homiletics, which is readily accessible. But, it is worth mentioning one circumstantial fact: Newman knew the congregation at St. Clement’s and that at Over Worton, and they knew him. This was of vital importance to Newman, given the value he placed on individual encounter and “personal influence.” The title of the sermon that perhaps most characterized his life, “Personal Influence, the Means of Propagating the Truth,”22 helps to convey this most Newmanian of principles. When he preached, he spoke to the heart and from the heart.23

Newman’s preaching program at St. Clement’s

Six weeks into his curacy, Newman succumbed to writer’s block. Having already begun a series of afternoon sermons on the parables, with enough material to last him at least four months, he decided to do the same for the morning service, based on a variety of themes. In this way he could deliver two sermons a week for the rest of his curacy. The first Sunday morning course, on the Trinity and man’s salvation, began on 12 September 1824 and finished two months later. There were eight other courses:

4 Advent sermons;

3 sermons on the hidden God;

6 sermons on faith;

6 sermons on Christ’s death and resurrection;

11 sermons on sin;

11 sermons on revelation and knowledge of the Gospel;

3 sermons on election of the Jews;

9 sermons on Jewish law and idolatry.

In addition to the afternoon course on the parables, there were nine other courses:

4 Advent sermons;

3 sermons on the Mediatorial Kingdom;

2 sermons on Joshua 24:4;

6 sermons on Psalm xxiii;

6 Easter sermons;

4 sermons on the Trinity, lukewarmness, secret faults, and conscience;

8 sermons on salvation and the future promise;

14 sermons on obedience to the law and the purposes of education;

6 sermons on the Gospel of St. Luke.24

So successful was the formula that he continued the practice at St. Mary’s, preaching another thirty courses.

No individual influenced Newman’s early sermons as much as Edward Hawkins, the fellow of Oriel who had been asked by the provost to take Newman under his wings in 1822. Hawkins, who was appointed vicar of the University Church in 1823, became a keen and able adviser to Newman on parochial matters. Twelve years apart, they were like pupil and tutor rather than colleagues, and never more so than when Hawkins carefully checked through Newman’s first sermons and gave him helpful criticism. It was by means of his arguments and illustrations from scripture that Hawkins helped to wean Newman away from his simple Calvinism and to see that the division of Christians between “real” and “nominal” was untenable.25 Hawkins also introduced Newman to the importance of tradition in the church, as well as the role of the ordinary Christian in passing on the faith.26

The geography of Newman’s prayer

It is helpful to round out the picture of Newman’s life at St. Clement’s by looking at his prayer intentions, for this is what gave unity to his life. Within the “geography” of his prayer – reflected in the framework he composed in 1824 – we can see the prominent place the parish occupied. Each day of the week had its own focus with themes and intentions itemized under three headings: 1) pray for, 2) pray against, and 3) intercede for. The pro forma for Saturday was devoted entirely to the parish. Under the general heading of “usefulness,” Newman wrote “success in preaching, visiting, calling, teaching, reading, catechizing,” before itemizing his intercessory petitions under four headings: 1) “In the parish,” 2) “In visiting the sick,” 3) “In catechizing,” and 4) “Towards dissenters.”

In addition, on Tuesdays, under “Intercede for,” appears: “flock at St. Clements, churchmen, dissenters, romanists [i.e. Roman Catholics], those without religion. […] Rector, churchwardens, and other offices. Sick, old, young, women labouring with child. Rich and poor, schools.” And under “Pray for,” he wrote “a blessing on my exertions, that the church be soon rebuilt and well.” On Thursdays, the scheme includes prayer for:

Judgement, discretion, tact, coolness, caution, presence of mind, decision, penetrations, discerning of spirits, invention of expedients, gift of conversation, moderation, full assurance of understanding, memory, power of application and illustration, gift of preaching both in soundness of speech and power of words.

On Fridays, he prayed for zeal – “Activity, diligence, perseverance, unconcernedness, undauntedness, resolution, firmness” – and against “indolence, lukewarmness, fear of man.” The following passage is effectively a prompt for meditation on his “sacred office” on Fridays:

A view to God’s glory, simple dependence on the grace of Christ, regarding myself as an instrument. For liveliness and fervency of prayer, for a deep sense of the awful nature of my sacred office, regarding myself as the voice of the people to God and of God to the people. For the spirit of devotion, affection towards my people, love, faith, fear, confidence towards God. For strength of body, nerves, voice, breath, etc. earnestness of manner, distinctness of delivery.

Intercessory prayer was also to include his family and relations, his benefactors, the provost and fellows of Oriel College, and other friends, even a prayer for “other Christian churches, for nominal Christians, for heretics, schismatics, papists etc; for Jews, for Mohammedans, for heathen.”27

Educational work and sermons

In the course of visiting his parishioners, Newman came into daily contact – for the first time – with poor people and their children, most of whom had never attended school. The more prosperous parishioners, such as shopkeepers, he observed, “have facilities for educating their children, which the poor have not – and on that ground it is that a clergyman is more concerned with the children of the latter.”28 For this reason, he set up a Sunday school, which began on 6 February 1825, with numbers restricted to forty children, due to lack of space and heating. Within a month he had raised money for and oversaw the enlarging of the church gallery so that ninety-four children could attend, while Pusey solved the heating problem by donating a stove. With the help of the rector’s daughter, Newman also organized four “book-lending circles.”29 It might seem surprising, but it was during his months at St. Clement’s that his educational ideas began to mature.

In a sermon preached shortly before his twenty-fifth birthday, Newman shows that he had thought deeply about the nature and purpose of education, and that he had already discerned in outline many of his key educational principles. Taking as his text “knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth” (1 Corinthians 8:1), words of St. Paul addressed to the Christians at the flourishing city of Corinth, Newman explained that, living among a highly civilized people, the Christians of Corinth fell into the error of “preferring knowledge to that warm and spiritual charity or love,” gifts to graces, the powers of the intellect to moral excellence. Newman pointed out that he and his congregation were living in parallel times, and he warned that the error of exalting human knowledge over Christian love would lead to the mistake “of supposing, that in proportion as men know more, they will be better men in a moral point of view,” and that a good education is a remedy for the world’s evil. Instead, “All education should be conducted on this principle – that it is a means towards an end, and that end is Christian holiness.” Moreover,

the object of education is to write the divine law upon the heart […] to prepare the heart for the gospel of Christ – it is to lead us to correct views of our own state and knowledge of our own hearts – it is to train us and win us over to habits of practical godliness, to accustom us to deny ourselves, to govern our passions, to fix our affections on God, and to trust Him with a humble and implicit faith.30

It is therefore “an error to suppose that the end of education is merely to fit persons for their respective stations in life,” since in that way “education is robbed of its religious character, and made the mere instrument of worldly ambition.” True, education concerns “the temporal callings of men, but it does not rest there.” The purpose of education is that people might so fulfil their respective occupations “as to make them the means of spiritual profit to their souls – we are preparing their souls, that their worldly trades and professions may affect them as they ought, may be the instruments of good to them […] preparing them to do good in their generation.”31

These insights are quite remarkable, for a number of reasons. They illustrate Newman’s conviction that everyone is called to Christian holiness; that living in the world is dangerous, not least for exalting worldly success over the acquisition of “habits of practical godliness”; and that a trade or profession could be the means of spiritual advancement and an opportunity to “do good in their generation.” But there is more. Newman urges that “parents should consider that from the earliest infancy of their children they are their natural guardians and instructors; that sending to school is merely an accidental circumstance, and but a part of education.” He went on to question the action of parents who think “they have done all that can be required of good and wise parents,” when they have sent their children to school at the proper age.32 This abiding conception of the educational task – that parents were the primary educators of their children – was to guide him when founding the first Catholic public school in Birmingham in 1859.33 The theme of fitting men for this world, while it prepares them for the next, runs through his educational classic the Idea of a University (1873) and informs his endeavors as founder and first rector of the Catholic University, which opened in Dublin in 1854.34

When Newman accepted the vice-principalship at St. Alban Hall, he had already begun to think his calling might be for college rather than parish – or even missionary – work.35 Now, in January 1826, after nine months of tutoring there, his mind was made up, and when invited to become a college tutor at Oriel, he accepted. Not only did he resign from St. Alban Hall, but he also gave up the curacy of St. Clement’s, justifying his decision on the grounds that the tutorship was a spiritual office and a way of fulfilling his Anglican ordination vows. What might appear as an excuse for merely indulging academic inclinations was, in Newman’s case, the result of several years of discernment, coupled with a conviction that the seventeenth-century idea of the college tutor could be revived. In the Laudian statutes of 1636,36 which were still in force, the role of the tutor was more associated with pastoral care than with secular instruction, and, although the tutor’s main task had become that of a college lecturer, enough of the old associations lingered on to convince most people that the task should continue to be undertaken by unmarried clergymen.

Newman’s Farewell Sermon

Newman took his last service at St. Clement’s on Easter Sunday 1826 and preached his farewell sermon a month later on 23 April. There is a marked difference in tone between his first sermon at Over Worton and his farewell sermon nineteen months later. During this time, the rigidity of his evangelical days had softened, and a more compassionate, but still demanding, pastor was in evidence.

Newman’s time at St. Clement’s was one of intense activity, and during it he underwent a profound change. He had arrived intent on changing the lives of his parishioners, but he left a changed man himself, transformed by the plain, working-class men and women he encountered. It is surely not an exaggeration to say that his dealings with the baker, brewer, and butcher forced him to clarify his theological ideas, which were incorporated into such works as his Lectures on Justification (1837); that his interest in the chandler, charwoman, and cook and their children helped him to formulate his educational ideas; and that his solicitude for the sick and dying gave him insights into the nature of religious belief that eventually found expression in his seminal philosophical work, the Grammar of Assent (1870).

1 Explanatory note (undated) accompanying his Packet of Sermons, St. Clement’s 1824–1826, Birmingham Oratory Archive [hereafter BOA], A.17.1.

2 Preface to John Henry Newman: Sermons 1824-1843 [hereafter Sermons], vol. v, ed. F. J. McGrath (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), viii.

3 Newman: AW, ed. H. Tristram (London: Sheed & Ward, 1956), 201.

4 Introduction, Sermons v, xxiv. The editor Frank McGrath suspects that the abstracts were written after the sermons were preached.

5 P. Doddridge, R. Graves, T. W. Horne, Z. Pearce, T. Scott, C. Simeon, G. Stanhope, J. B. Sumner, J. Trapp, and D. Whitby.

6 AW, 202.

7 (3 September 1824), AW, 202.

8 (14 June 1864), AW, 201.

9 (21 February 1825), AW, 204. Newman refers to Thomas Scott and his Holy Bible; with explanatory notes, practical observations, and copious marginal references (1814, 6 vols) and his Force of Truth (1817). Newman describes Scott as “the writer who made a deeper impression on my mind than any other, and to whom (humanly speaking) I almost owe my soul” in the Apologia pro Vita Sua (1865), 5.

10 (8 December 1824), LD i, ed. I. Ker and T. Gornall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), 203n.

11 The two copies of the Speculum Gregis can be found in BOA, A 12.3.

12 Newman to his father (9 August 1824), LD i, 184.

13 Newman to his father (9 August 1824), LD i, 184.

14 Newman follows the simple ritual in the Book of Common Prayer for “The Thanksgiving of Women after Child-Birth, commonly called, The Churching of Women.” As most families in the parish were large, churchings were regular events.

15 (14 January 1826), LD i, 272.

16 (20 July 1824), LD i, 179.

17 (25 July 1824), LD i, 179–80.

18 Ian Ker, Newman: His Life and Legacy (London: CTS, 2010), 13.

19 “Wait on the Lord,” Sermons v, 5–6.

20 “Wait on the Lord,” Sermons v, 7.

21 (19 October, 25 November 1823), AW, 194–95.

22 This sermon, preached on 22 January 1832, can be found in his Oxford University Sermons.

23 For more on this, see John F. Crosby, The Personalism of John Henry Newman (Washington: Catholic University of Press, 2014), 66–87.

24 The list of sermon courses at St Clement’s can be found in appendix IV, Sermons v, pp. 447–51.

25 Besides remarking on it being “unreal,” Newman comments that “Calvinism was not a key to the phenomena of human nature, as they occur in the world.” AW, 79.

26 This is a major theme in Hawkins’s sermon “The use and importance of unauthoritative tradition as an introduction to the Christian Doctrine,” preached on 31 May 1818 (London: Rivington, 1819). Newman heard this sermon and recounts in the Apologia (p. 9) how deeply influenced he was by it.

27 BOA, A 10.4. Another version of this list of petitions can be found in V. F. Blehl, Pilgrim Journey: John Henry Newman 1801–1845 (London: Burns & Oates, 2001), 419–23.

28 Newman to his father (9 August 1824), LD i, 184.

29 (1 September 1825), LD i, 255–56.

30 “On Some Popular Mistakes as to the Object of Education,” preached on 8 January 1825, Sermons v, 368–70.

31 “On Some Popular Mistakes as to the Object of Education,” 371.

32 “On Some Popular Mistakes as to the Object of Education,” 369, 372.

33 For more, see Paul Shrimpton, A Catholic Eton?: Newman’s Oratory School (Leominster: Gracewing, 2005).

34 For more, see Paul Shrimpton, The ‘Making of Men’: the Idea and Reality of Newman’s University in Oxford and Dublin (Leominster: Gracewing, 2014).

35 On accepting the vice-principalship, he wrote in his journal, “I have all along thought it was more my duty to engage in College offices than in parochial duty. On this principle I have acted.” (26 March 1825), AW, 205.

36 The Laudian Code decreed that the tutor should imbue the students committed to his charge with good morals and instruct them in approved authors, above all in the rudiments of religion and the Thirty-nine Articles. He was also to be responsible for his students’ behavior.

Share

Paul Shrimpton

Paul Shrimpton teaches at Magdalen College School, Oxford. Over the last thirty years he has published articles, chapters and books on Newman and education. His Newman and the Laity will appear in 2025.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS