A Sermon on Newman as a Saint

This sermon was preached for the Memorial of St John Henry Newman on Wednesday 9 October 2024 in the Metropolitan Cathedral and Basilica Church of Ss Peter and Paul, Philadelphia, during a Mass celebrated according to Divine Worship, the missal approved for use by former Anglicans who have entered the full communion of the Catholic Church.

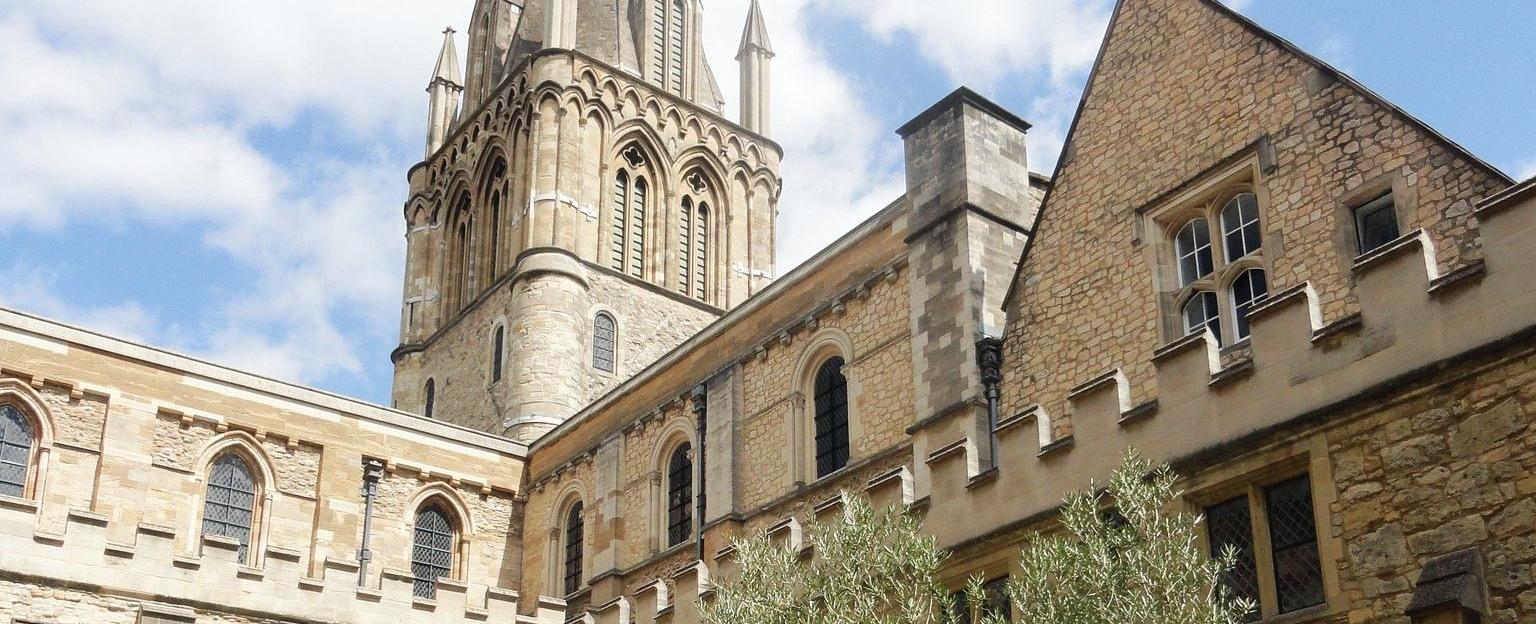

Two hundred years ago, on 13 June 1824, the young Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, who today the Church celebrates as a saint, made his way down the High and St. Aldate’s with his surplice and his MA hood, to be made a deacon of the Church of England in Christ Church Cathedral, the former medieval nunnery and shrine to St. Frideswide until Thomas Wolsey chose it to become Cardinal College in 1525.

Of that morning’s events, celebrated according to the rites and ceremonies of the Book of Common Prayer and at the hands of the seventh son of the Earl of Dartmouth—the Bishop of Oxford, Edward Legge—the Reverend John Henry Newman recorded in his diary, simply: “Ordained Deacon in Christ Church.”1

Elsewhere he wrote more fully, even movingly of the occasion: “It is over,” he said, “I am thine, O Lord; I seem quite dizzy, and cannot altogether believe and understand it. At first, after the hands were laid on me, my heart shuddered within me; the words ‘for ever’ are so terrible. It was hardly a godly feeling which made me feel melancholy at the idea of giving up all for God. At times indeed my heart burnt within me, particularly during the singing of the Veni Creator. Yet, Lord, I ask not for comfort in comparison of sanctification.”2

The new Curate of St. Clement’s went the following Wednesday, not to his title parish in the wilds of Oxford that one encounters after crossing Magdalen Bridge, but to Holy Trinity, Over Worton; a church some seventeen miles north of the city, where his old schoolmaster and convinced evangelical, Walter Mayers, was the incumbent. Here Newman gave the first of his sermons; texts that have come to define not only his personal faith and spiritual odyssey, but the very rhetoric and quality of English religious writing for much of the following century. So prodigious was Newman’s preaching output, that in the mere 19 months of his curacy at St. Clement’s he composed and delivered some 150 distinct sermons.3

This concern for preaching was not limited, however, to words from a pulpit. A month after his arrival in the parish of the elderly rector, John Gutch, the more youthful and energetic Newman began a concerted series of pastoral visits to the homes of his parishioners. He recorded the hundreds of calls he made in a little book, noting the name, occupation, age, health, and spiritual condition of those he met. It was during one of these visits that he encountered Fr. Robert Newsham, who served the Oxford Mission, and whose Mass Newman would attend on 12 October 1845, just three days after his reception into the full communion of the Catholic Church.

These historical details of Newman’s life, and to some Catholic ears the almost (perhaps) irrelevance of his ordination and ministry in the Church of England, might seem to us anecdotes more fitting to a lecture or recollection, than a sermon. But in considering the example and significance of John Henry Newman as our saint, as we are bound to do by the Church on this his liturgical feast, it is precisely these hints and indications of the operation of the Holy Spirit in the life of the man that help us to understand more fully the miraculous transformation that took place within him, and which—through his inspiration and by his intercession—we might also begin to trace in our own lives.

Amidst all the frippery and Romantic emotionalism in Newman’s recollection of his Anglican ordination, there is one line that stands out and cuts to the quick: “Lord, I ask not for comfort in comparison of sanctification.” This little prayer seems to embody in its brevity and simplicity, the ultimate purpose and lifelong intentions of this great—and, we may add with confidence, holy—man.

For the same trembling ordinand who knelt on the chequerboard floor of Christ Church on that English summer’s day in 1824, filled with trepidation at the prospect of (in his words) “giving up all for God,” felt and experienced so much of the cost of that transaction, not through the more radical shedding of his blood like the many martyrs of his homeland who went before him, but rather in the at-times lonely, and very often misrepresented search for the truth, that led him at length to “the one true fold of the Redeemer.”4

It is perhaps the close correlation of his thought and action that makes Newman’s example so convincing, and indeed so compelling to the many who in our own time have found themselves—again, as he put it—“shivering at the gates” of the Catholic Church, and asking to come in.5 As one notable person put it at the time of his canonization: Newman “not only proved this [conviction] in his theology and illustrated it in his poetry, but he also demonstrated it in his life.”6

What is it, then, that ultimately he showed? It was that simple prayer: to seek not comfort in this life, but sanctification. To listen for, to follow, and to seek out, the echoes of the heart of Jesus Christ, until they resounded with such closeness and fervor that they became indistinguishable from his own; truly, heart speaking to heart. And to follow his conscience—not as a beguiling phantasm that morphs according to one’s immediate inclinations—but as “the prerogative of commanding obedience”7; “a dutiful obedience to what claims to be a divine voice, speaking within us” and leading us ultimately to the truth.8

Newman knew well that the final end of his intellectual pursuit of the truth was not mere knowledge, nor even the satisfaction of an argument won, but holiness. He knew, as St. Paul knew, and as we have heard tonight, that “no one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God” (1 Cor. 2:11); that truth comes from God, and ultimately leads to God. As Newman put it: “To be holy is. . .to be separate from sin, to hate the works of the world, the flesh, and the devil; to take pleasure in keeping God’s commandments; to do things as he would have us do them; to live habitually as in the sight of the world to come, as if we had broken the ties of this life, and were dead already.”9

To live as if we had broken the ties of this life for our saint meant the parting of friends, social exile, ridicule, and even persecution through the weaponization of the courts. It meant to live habitually as in the sight of the world to come and to be concerned therefore not with the praise and adulation of one’s peers, but to seek only the crown of righteousness that comes from God alone as the reward for a faithful and definite service.

St. John Henry Newman’s fidelity to the holiness of Christ led him, one step at a time, on a journey deeper and deeper into the heart of the Catholic Church and true religion. His intellectual pilgrimage from evangelicalism, to the furtive but ultimately hopeless attempts to justify the Catholic claims from within Anglicanism, urged him on to find in the Church of Rome the apostolic foundations to which his academic curiosity had summoned him for so many years. In his submission to and subsequent living out of that truth, then, Newman embodied both extraordinary theological and spiritual gifts, in a manner that the Church has often identified in those whom she honors with the noble title, Doctor ecclesiae universalis.

The writings of these saints and Doctors of the Church are considered to have a special authority on account not only of their erudition, but also—more importantly—their universal and perennial value. We must therefore give thanks to God that so many of the successors of the apostles in our own day have seen fit to identify in the life and work of St. John Henry Newman such merit as to petition that he be declared, along with those other great Englishmen—St. Anselm and the Venerable Bede—a Doctor of the Church. And we might join our hearts to their petition in the hope that the Church, to which our saint dedicated so much of his life, might give authority to such a claim, and permit us to add to our veneration of his example the confidence of knowing the profit of his writings.

For those of us who have found the kindly light of truth by tracing for ourselves the footsteps of John Henry Newman, and finding our own way home to the Catholic Church, the twin lights of his mind and heart have already been a sure means to arrive at the fullness of life in Jesus Christ as very members incorporate in his mystical body, the Church. We are, we might say with a certain sense of pride, heirs to Newman’s legacy and inheritors of the wisdom and courage he embodied in his own journey ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem. But we must take care not to be selfish in holding too tightly the gifts that our saint has left us as fellow ‘converts.’ For to whatever extent he has helped us to find the truth of the Catholic religion and the certainty of the doctrine she expounds, his writing and example deserves a yet wider audience; that others might come to acknowledge the treasure they already possess, and so live more fully and completely the life of the Redeemer, in and with the Church which he himself founded.

May St. John Henry Newman pray for us, and most especially for the work of the ordinariates.10 May his witness be an inspiration for all who seek the fullness of the gospel with humility and with sincere devotion. And may we ask the good Lord that this servant and disciple of Christ the master teacher soon be granted a place amongst the Church’s doctors, that by this sign his example may gain greater appreciation, through his word and example rooted in Jesus Christ, and thereby draw yet more souls into “the one true fold of the Redeemer.”

1 Newman, diary entry for 13 June 1824, LD I, 177.

2 Henry Tristram, ed., John Henry Newman: Autobiographical Writings (London: Sheed & Ward, 1956) 200.

3 Paul Shrimpton, “Bicentenary of Newman’s First Sermon,” Newman Review (19 June 2024).

4 Newman, “Letter to Henry Wilberforce” (7 October 1845), LD xi, 3..

5 Newman, “Letter to Ambrose Phillipps de Lisle” (27 January 1876), LD xxviii, 20..

6 Charles, Prince of Wales, “John Henry Newman: The harmony of difference,” L’Osservatore Romano.

7 Newman, Duke (New York: The Catholic Publication Society, 1875), 72.

8 Newman, Duke, 80.

9 Newman, “Holiness Necessary for Future Blessedness,” PS i, 2–3.

10 Benedict XVI, apostolic constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus (4 November 2009), AAS 101 (2009): 985–90.

James Bradley

James Bradley is Assistant Professor of Canon Law at The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, and a Priest of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.

QUICK LINKS