A Model for Encountering Others in the Correspondence of Newman and Froude

St. John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801–1890) exemplifies what it means to learn with and from others. Before becoming Catholic in 1845, Newman had ascribed to the Evangelical party and then later the High Church party of Anglicanism. It was through certain friendships penetrating his heart so deeply that he became attracted to the truths of the Catholic faith. When Pope Leo XIII made Newman a cardinal in 1879, Newman chose cor ad cor loquitur (Heart speaks unto heart) as his motto.1 His friends surely spoke to his heart, and his heart spoke to theirs. Newman’s example demonstrates the importance of encountering others, and this is needed perhaps now more than ever.

During Newman’s time, it was not possible to contact others almost instantaneously as we can today. Newman spent time with his friends in-person when at Oxford and these friendships had an enormous impact on his growth in faith and understanding. Newman’s primary way of sustaining these relationships when he could not see his friends in person was through deep, meaningful, written correspondence often about theological topics. Today, social media platforms keep people linked to a vast network of people, but oftentimes the interactions are minimal. Instead of calling someone and engaging in conversation, the modern tendency is to send a rushed email or text message. Furthermore, new information is acquired through apps, podcasts, the internet, or AI instead of using our personal connections as resources. Technology cannot be the sole means of gaining understanding because we will only learn partial truths in this way.

St. John Henry Newman believed that human beings must spend time with others and have a faith that is rooted in their love for God to understand the Truth more deeply.2 To Newman, faith is “reasoning of a religious mind” (an exercise of reason) and is only protected from abuse or error by a heart burning with love for God.3 It is through spending time with others—hearts speaking unto hearts—that the Gospel message is spread and we can develop this burning love for God. Newman has been referred to as “an apostle of friends,”4 because he exemplified one who did not shy away from fruitful and challenging conversations in person or through his written words, which enabled him to productively pursue the Truth. This “Man of Letters,” wrote over 21,000 letters to family, friends, his fellow clergy, and acquaintances. Newman’s written words were self-referential, allowing his own heart to speak to other hearts but also vulnerably opening his heart to the ideas of others.

It was through the bonds of friendship that Newman became involved in the Oxford Movement (1833–1845)—an attempt by clergymen and scholars at Oxford University to correct shortcomings in the Anglican Church by returning to some Catholic traditions of the early church. Newman became one of the most famous leaders of this movement, which would become a defining period in his life. The leaders of the Oxford Movement inspired one another and personally influenced one another.5 Throughout the movement, Newman’s heart was touched by the hearts of his friends and their inspiration in no small way contributed to his conversion to the Church of Rome in 1845. One friend, Richard Hurrell Froude, would particularly move Newman’s heart to open itself up to the truths of the Catholic faith. However, Newman was not immediately accepting of some truths of the Catholic faith in large part due to the anti-Catholic climate in nineteenth-century Great Britain.

Newman’s Anglican Resistance to Catholicism

In the nineteenth century, Catholics were viewed with distrust because they had allegiances to both the British crown and to the Vicar of Christ. British Anti-Catholicism or “No Popery” was aimed against Catholic doctrines and was not just against abuses of the clergy as it was in continental Europe. As a Catholic, Newman explained the Anti-Catholic temperament in nineteenth-century England: “When a person goes to a fever ward, he takes some essence with him to prevent his catching the disorder; and of this kind are the Anti-Catholic principles in which Protestants are instructed from the cradle.”6 Consequently, Anglicans tried to social distance themselves from the presumed disorders of the Catholic religion not only to avoid being “infected” with Catholic doctrines but out of fear of being charged with holding Catholic sentiments. To avoid being accused of this “Popery,” Newman confessed that he said as much as possible against the Church of Rome when he was an Anglican.7

Furthermore, Marian devotion and dogmas had been one of the major areas of discord between Catholics and English Protestants since the Reformation and was an identity marker for Catholics that Anglicans did not want. Even though members of the Oxford Movement aspired to restore certain facets of Catholicism to the Church of England, some of them were not willing to breakdown this major barricade of devotion to the Virgin Mary and accordingly be accused of “popery.” Newman was no different. As an Anglican, he condescendingly labeled Marian devotion as “Mariolatry” and reflected as a Catholic that this had been his great “crux” to him initially being able to enter the Church of Rome.8

Even though Newman tried to protect himself from the supposed abuses and corruptions of the Catholic Church in the form of Marian devotion as an Anglican, he was still suspected of holding a “papist” doctrine related to the Virgin Mary. In his sermon “Reverence Due to the Virgin Mary” (1832), Newman was accused of assenting to the Catholic belief in Mary’s Immaculate Conception.9 Perhaps partly to defend himself, Newman explicitly declared in a sermon the following year that “Mary, His Mother, was a sinner, as others, and born of sinners.”10 Thanks to Newman’s dear friend and collaborator in the Oxford Movement, Richard Hurrell Froude, his attacks on the Catholic Church and its forms of Marian piety would not last.

Richard Hurrell Froude

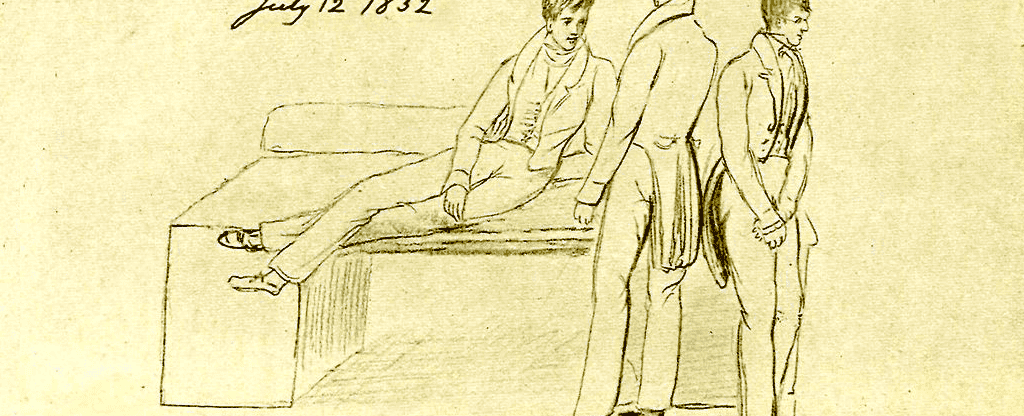

Froude and Newman became friends while they were both fellows at Oriel College.11 Their conversations penetrated the surface of important issues of the day and allowed the two men to truly get to know one another. Newman spoke of Froude as having “gentleness and tenderness of nature … and … patient winning considerateness in discussion, which endeared him to those to whom he opened his heart. … His opinions arrested and influenced me, even when they did not gain my assent.”12 Froude’s demeanor was inviting and comfortable, and his words captured the attention of Newman. Froude and Newman did not just occasionally speak. They travelled together along with Froude’s father to the Mediterranean from 8 December 1832 to 9 April 1833.13 They continued to communicate through written correspondence when Froude visited the West Indies in 1835.

It is only through the fostering of their friendship and truly listening to one another that their hearts were able to speak to one another and bear much fruit, particularly in Newman. First, Froude condemned Newman for his verbal attacks on the Catholic Church, even though Newman was doing it to protect himself.14 Froude never converted to Catholicism, but he had a great affinity for the medieval church.15 Newman never developed an allure for medieval forms of piety, but he never forgot the witness of Froude’s great love for the medieval church. Newman was eventually attracted to the Catholic Church and became a defender of the church.

Second, Froude did not hesitate to express his antipathy for the Protestant Reformation, its destruction of Catholic worship, and lack of reverence for tradition.16 In particular, Froude was drawn to medieval forms of Marian devotion. Newman was at first not accepting of Froude’s admiration for Marian devotion because he did not believe it was rooted in the teachings of the early church.17 But, Froude instilled the idea of a devotion to Mary in him, which stayed with Newman even after Froude’s untimely death in 1836. Froude’s assent to Marian devotion motivated Newman to investigate the origins of the Immaculate Conception, and he found that this dogma was rooted in the church fathers’ conceptions of Mary as the New Eve.18 Newman was able to overcome his major hindrance to being able to enter the Church of Rome and his fear of Mariolatry. It was not just a stranger’s love of Mary that first moved Newman’s heart to explore the truths of this Marian dogma in the first place, but his dear friend Froude. Newman attributed his deep devotion to the Virgin Mary to his departed friend.19 Newman’s Marian devotion came first and then came Newman’s intellectual assent to the Catholic Marian dogmas.

It is highly probable that Newman would never have “freed himself” from his prejudices against the Catholic Church if it had not been for the influence of Froude.20 Years later, Newman pondered: “It is difficult to enumerate the precise additions to my theological creed which I derived from a friend to whom I owe so much. He taught me to look with admiration towards the Church of Rome, and … fixed deep in me the idea of devotion to the Blessed Virgin.”21 Newman never developed a love for medieval, Marian piety like Froude, but thanks to Froude, his Marian devotion grew enough for him to willingly enter into communion with the Church of Rome.22

Newman’s friendship with Froude is a powerful example of Newman’s famous motto: cor ad cor loquitur. Even though Newman’s conversion was ultimately of an intellectual nature, it was his heart that was touched first by Froude. His mind just needed to agree with his heart, which had an increased affection for the Virgin Mary. We need to be intentional about cultivating lasting friendships and encountering others in authentic ways and not just behind screens. Newman wrote in a prayer: “I am a link in a chain, a bond of connections between persons.”23 St. John Henry Cardinal Newman’s heart is still linked to ours as it speaks to us through his many works and when he intercedes for us. Let it be our mission to build friendships where our hearts speak unto other hearts in such a powerful way that the Catholic faith is passed on and embraced by others.

1 Nicholas L. Gregoris, “The Daughter of Eve Unfallen”: Mary in the Theology and Spirituality of John Henry Newman (Pine Beach, NJ: Newman House Press, 2003), 28.

2 Newman, “The Nature of Faith in Relation to Reason,” US (Rivingtons: London, 1880), 203.

3 Newman, “The Nature of Faith in Relation to Reason,” US, 203.

4 “Full Interview: Scott Hahn on the Apostle of Friendship, St. John Henry Newman,” St. John Henry Newman Canonisation Resource.

5 Christopher Dawson, The Spirit of the Oxford Movement (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2023), 12–13.

6 Newman, Lectures on Present Position of Catholics in England, 2nd ed. (London: Burns and Lambert, 1851), 353.

7 Newman, Apo (London: Penguin Books, 1994), 66.

8 Newman, Apo, 179.

9 Newman, “Memorandum on the Immaculate Conception,” MD (London: Longmans, Green, and Co. 1916), 79, 87. Note: The Immaculate Conception was not promulgated as a dogma of the Catholic Church until 1854, which was 22 years after Newman gave this sermon.

10 Newman, “The Incarnation,” PS ii, 32.

11 Newman became a Fellow in 1822, and Froude became a Fellow in 1826.

12 Newman, Apo, 152.

13 Sheridan Gilley, Newman and His Age (London: Cromwell Press, 2003), 94, 103.

14 Newman, Apo, 66.

15 Newman, Apo, 42.

16 Newman, Apo, 41.

17 Gregoris, “The Daughter of Eve Unfallen,” 362.

18 R. James Lisowski, C.S.C. “Newman’s Mature Mariology,” Newman Studies Journal 19, no. 1 (2022): 28, 34.

19 Newman, Apo, 42.

20 Dawson, The Spirit of the Oxford Movement, 37.

21 Newman, Apo, 42.

22 Newman, Apo, 179.

23 See Fr. Billy Swan, Newman, “Unpacking One of Newman’s Gems.”

Erin Meikle

Student, Duquesne University

Erin Meikle is a doctoral student in Theology at Duquesne University. She previously earned a B.S. in Mathematics from the Pennsylvania State University, a Master of Arts in Teaching from the University of Pittsburgh, a Ph.D. in Education—mathematics education specialization—from the University of Delaware, and a Master of Arts in Theology from Duquesne University. Erin's current research includes exploring topics in Mariology and John Henry Newman's educational theory and practice.

QUICK LINKS