A Chapel, a Desk, and One Man's Saintly Witness - Reflections on the Canonization of John Henry Newman

As someone who has studied John Henry Newman's writings for years, it was surreal for me to attend his canonization in Rome. I've known for some time now that Newman was interceding for me and my loved ones in heaven, but to have a tangible confirmation of that fact was moving beyond words. The entire experience profoundly reinforced for me the reality of the communion of saints. Thousands of pilgrims from around the world gathered in St. Peter's Square to celebrate the working of God's grace in the lives of Saint John Henry and four holy women—Mother Giuseppina Vannini, foundress of the Daughters of St. Camilo; Sister Mariam Thresia Chiramel Mankidiyan, foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family; Sister Dulce Lopes Pontes, the first Brazilian-born female saint; and Margherita Bays, a humble seamstress. Even though these holy persons have already passed on to their reward, we remain in communion with them as fellow members of the mystical body of Christ. Several of the pilgrims whom I spoke to testified to the fact that their faith would not be what it is today without the prayerful support of these heavenly intercessors.

The trip also gave me a stronger recognition of the lifeblood that flows from the rich history of our Catholic faith. Our practice of the faith would not be what it is today without the sacrifices and witness of the many saints who have preceded us. It is one thing to recognize that idea in the abstract; it's quite another to come into contact with tangible monuments to that reality. In Rome and Littlemore and Birmingham, we walked where Newman had walked, we touched the stones of a church he had designed himself, and (perhaps most moving of all) we prayed in his private chapel—the very room in Birmingham where he daily offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Over the past dozen years, I've come to know Saint John Henry via the written word. Through this pilgrimage, I grew to know him on a deeper level, by seeing and touching the artifacts of his extraordinary witness to the truth of the Gospel.

Saint Thomas Aquinas tells us that grace does not destroy but builds on and perfects nature. What this means in part is that, when God sanctifies us, He does not do away with or replace our natural gifts and personality. Rather, God takes us, as we are, and elevates our nature to a supernatural level. This was certainly evident in Saint John Henry's life. God took Newman's bookishness as well as his literary giftedness and used them to draw many sinners to conversion. Heart indeed speaks to heart, and when we open our lives fully to the working of God's grace, then the Divine heart can move the hearts of others through whatever meager gifts we are able to offer ad majorem Dei gloriam—to the greater glory of God.

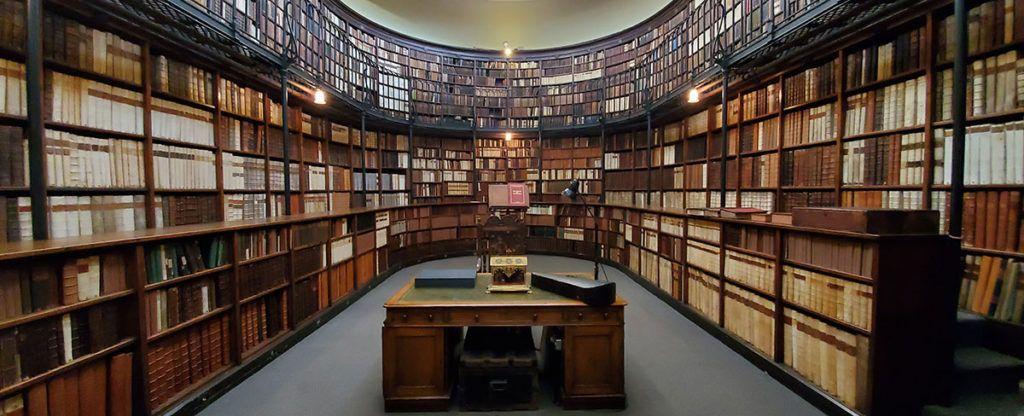

This point was driven home to me in a special way when we visited Littlemore, a small villa on the outskirts of Oxford, where Newman established a quasi-monastery while on his "Anglican deathbed." During our visit there, we had the privilege of seeing firsthand the standing desk at which Newman contemplated going over to Rome and at which he penned his famous Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Now that he is a saint, such objects are rightly considered second-class relics by the faithful who take pilgrimages to the site. Seeing that we were impressed, our tour guide went on to inform us that the desk had been used as an altar by Blessed Dominic Barberi, the Italian Passionist priest who received Newman into the Catholic Church, because there was no permanent Catholic altar on the precincts. In other words, Saint John Henry's first holy communion took place at a Mass celebrated on that very desk. After the day of his conversion (9 October 1845), Newman never again used the desk—and understandably so! What had formerly been a mundane object used for study and writing had now been consecrated to God by virtue of its use in the most sacred of ceremonies. It would be wrong, Newman concluded, to return the desk to its former use.

As I stood there and reflected on all of that history, the desk struck me as a powerful reminder of the significance that our lives can have if we will only offer ourselves completely to the things of God. Here before me was a work of human craftsmanship that had been transformed from tree to desk to altar, and upon which had been celebrated the greatest act of adoration that human beings are able to offer God. In his loving providence, the Almighty had taken the ordinary elements of the natural world and drawn them up into the divine economy, making possible a true communion between God and humankind. For me, the desk was symbolic of Cardinal Newman's entire life. He could have used his many talents in all sorts of ways to benefit himself, but instead he chose to turn them over completely to God's service. As we reflect during these days on Newman's heroic example, let us ask God to extend to us the same grace that He extended to the Cardinal, so that we too can become saints—little Christs who mediate God's love to a world that is so desperately in need of it.

Share

Ryan Marr

Associate Provost at Mercy College of Health Sciences, Iowa

Ryan ("Bud") Marr Associate Provost at Mercy College of Health Sciences. He has served as the Director of NINS and Associate Editor of the Newman Studies Journal from 2017-2020. He is the author of To Be Perfect Is to Have Changed Often: The Development of John Henry Newman's Ecclesiological Outlook, 1845–1877 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), and has also contributed essays to Newman and Life in the Spirit (Fortress Press, 2014), Learning from All the Faithful (Pickwick, 2016), and The Oxford Handbook of John Henry Newman (Oxford University Press, 2018). His research interests include the life and writings of John Henry Newman, ecclesiology, and the reception of Vatican II.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS